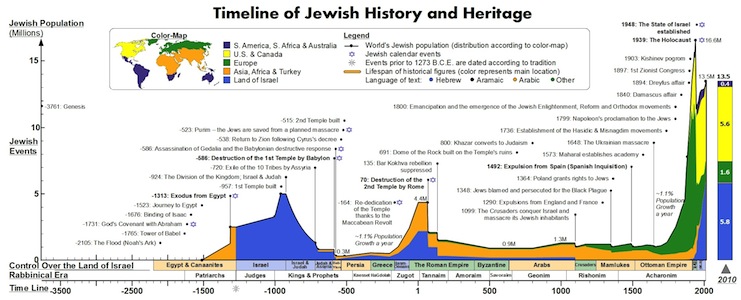

I will only scratch the surface of this huge subject by pointing out the importance of textual continuity through 5,000 years of Jewish history.

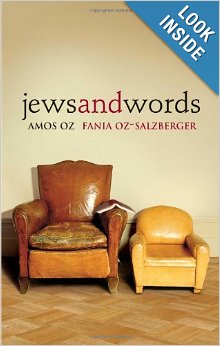

The subject of Jewish textual continuity, or the “textline” (analogous to bloodline), has recently been introduced by secular Israeli novelist Amos Oz and his daughter in a fantastic and innovative joint book called Jews and Words.

I want to focus specifically on the textline as it relates to the Land of Israel, which is a narrower focus than Oz’s book.

In The Beginning…

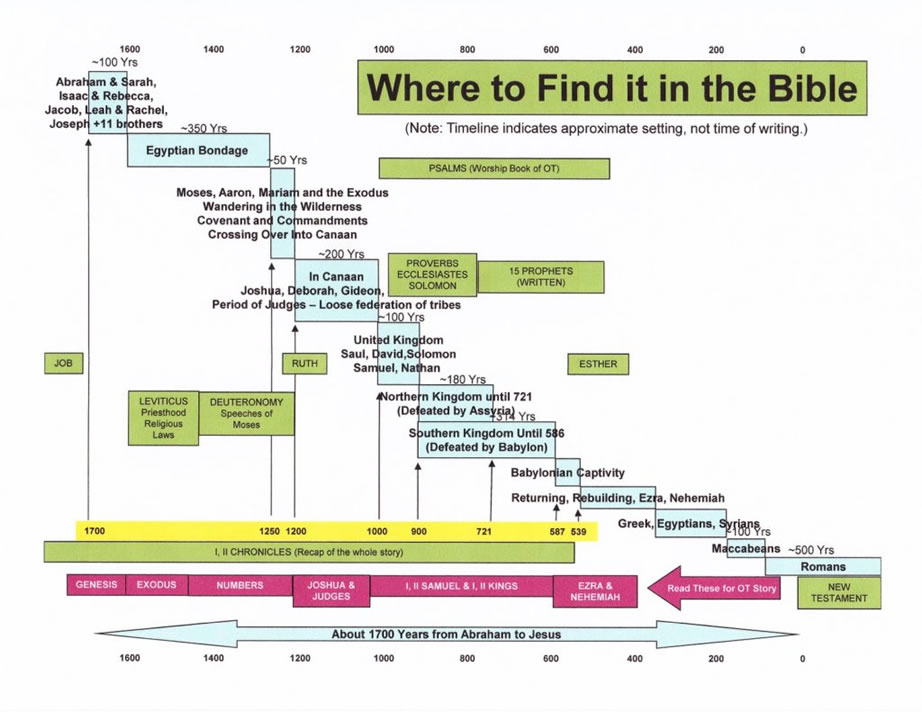

To open this subject, I sometimes ask people: what is the plot of the Tanakh (תנ”ך)? I mean, if you read it cover to cover in chronological order, how would you summarize the plot? And just to make it easier, I will ask you to skip the first 11 chapters of Genesis and start from Lech Lecha (לך לך): Abraham’s journey to Israel.

It’s obvious, isn’t it? It’s a collection of the formative stories of the Jewish people in their land. Abraham makes Aliyah from Mesopotamia, buys the Cave of Machpelah, goes to Egypt, comes back. Jacob goes back to Mesopotamia, returns to Israel, Joseph goes to Egypt. Slavery. Moses frees the Jews from Egypt and leads them to the land of Israel, but does not enter. Joshua conquers the land. The Judges institute the rule of law. Saul becomes king. David becomes king, conquers Jerusalem, buys the Temple Mount site (which is Mount Moriah) from Arunah the Jebusite, and Solomon builds the First Temple at the same location. Around 721BC, Assyria exiles the 10 Northern tribes and replaces them with the Samaritans. The Northern Kingdom is lost forever, but Judea remains Jewish until 586BC when the Babylonians destroy Jerusalem and exile most of the Judeans.

First Return to Zion

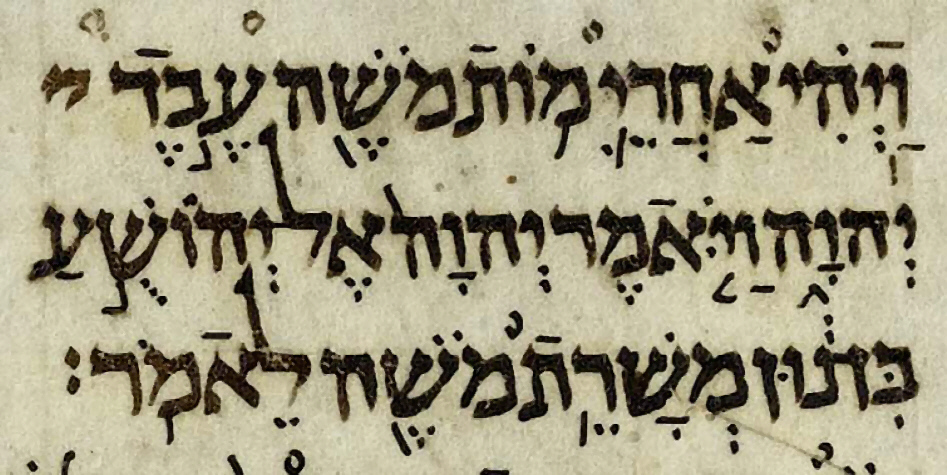

But, luckily, the story doesn’t end there. Around 538BC, King Cyrus issues his decree to allow Judeans (Jews) to return to Israel and rebuild Jerusalem. The Cyrus Decree in the Bible is in the book of Ezra:

“Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth has Adonai, the God of heaven, given me; and he has charged me to build him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whosoever there is among you of all his people, his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem, which is in Judah, and build the house of Adonai, the God of Israel he is God, which is in Jerusalem.” (Ezra 1:2-4; cf. also 6:2-5).

The Cyrus Decree is archeologically corroborated by the famous Cyrus Cylinder.

The biblical book of Nehemiah is especially worth reading, as it demonstrates the emotional bond between the Jews and the land of Israel even back then. Nehemiah is well-off, living happily in Shushan (the city of Purim) when he hears that “the wall of Jerusalem is breached, and its gates were burned with fire”. He cries and mourns, and finally springs into action. He makes Aliyah and organizes the Jews to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls. Just as in modern times, when some local nomads hear that the Jews are rebuilding the walls they react violently (Nehemiah 4): “Now it came to pass when Sanballat, and Tobiah, and the Arabs, and the Ammonites, and the Ashdodites heard that the wall of Jerusalem was repaired, that the people who were exposed had commenced to be closed in, that they became very angered. And they all banded together to come to wage war against Jerusalem and to wreak destruction therein”

In spite of the attacks, the Jews succeed in rebuilding the walls, while taking turns defending themselves, and in Nehemiah 8 they celebrate their victory by doing what Jews do at synagogue until this very day: reading the Torah and interpreting it in a communal setting:

Now all the people gathered as one man to the square that was before the Water Gate, and they said to Ezra the scholar to bring the scroll of the Law of Moses, which the Lord had commanded Israel. And Ezra the priest brought the Law before the congregation, both men and women, and all who could hear with understanding, on the first day of the seventh month. And he read in it before the square that was before the Water Gate from the [first] light until midday in the presence of the men and the women and those who understood, and the ears of all the people were [attentive] to the Scroll of the Law.

For an important archeological corroboration of the Ezra-Nehemaiah story, please see my article on the Jews of Elephantine who celebrated Passover during the time of Nehemiah.

The Bible leaves off after Jerusalem is revived from its desolation and the Second Temple is built.

From Bible to Mishnah

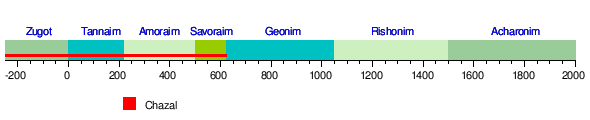

But, contrary to what some people think, the Jewish textline, as it relates to the land of Israel, does not end with the Bible. Quite the opposite. The post-biblical period is called the period of Chazal (the sages), and it is characterized by a vast array of innovative texts, all built on the biblical foundation and on each other. The Wikipedia timeline below shows the collective names given to the sages and authors during each of the different periods that followed the Bible.

The earliest next book in the chain is Pirkei Avot, whose very first chapter establishes the continuity.

The earliest next book in the chain is Pirkei Avot, whose very first chapter establishes the continuity.

“Moses received the Torah from Sinai and gave it over to Joshua. Joshua gave it over to the Elders, the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets gave it over to the Men of the Great Assembly…Shimon the Righteous was among the last surviving members of the Great assembly…Antignos of Socho received the tradition from Shimon the Righteous…Yossei the son of Yoezer of Tzreidah, and Yossei the son of Yochanan of Jerusalem, received the tradition from them… Joshua the son of Perachia and Nitai the Arbelite received from them…Judah the son of Tabbai and Shimon the son of Shetach received from them…Shmaayah and Avtalyon received from them…Hillel and Shammai received from them…Rabban Gamliel would say…His son, Shimon, would say…”

How was this tradition passed down? By years of intense text and oral tradition studies at Yeshivas in the land of Israel, and by studying the deliberations and judgements of the Sanhedrin. The period covered in this lineage is called the Zugot (pairs) because two sages stood at the head of the Sanhedrin; one as president (“nasi”) and the other as vice-president or father of the court (“Av beit din”).

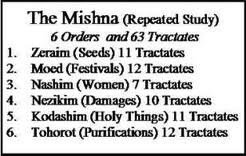

Pirkei Avot is just one small part of the Mishnah, which was redacted by Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi (Judah the Prince) in the land of Israel around the year 200 CE. Most of the Mishnah is translated online. All the sages mentioned above in the opening chapter of Avot, as well as the later Tannaim, play important roles in the Mishnah. For example, I mentioned Shimon Ben Shetach in a previous post about Choni ha-M’agel.

So, you see, the Mishnah, which builds on top of the Bible, was written in Hebrew, in the land of Israel, and establishes the textline from around 300BC, which is around the end of the Bible chronology, up until the 2nd or 3rd century CE.

But it’s not just the continuity of the textline which is important. It’s also its content. Many parts of the  Mishnah are concerned with rules and practices which are specific to the land of Israel and the Second Temple. For example, Pe’ah (field corner designated for charity) is the second tractate of Seder Zeraim (“Order of Seeds”) of the Mishnah. This tractate begins the discussion of rules related to agricultural gifts to the poor, which apply only in the land of Israel. This is how we know that the Mishnah could not possibly have been written anywhere other than the land of Israel:

Mishnah are concerned with rules and practices which are specific to the land of Israel and the Second Temple. For example, Pe’ah (field corner designated for charity) is the second tractate of Seder Zeraim (“Order of Seeds”) of the Mishnah. This tractate begins the discussion of rules related to agricultural gifts to the poor, which apply only in the land of Israel. This is how we know that the Mishnah could not possibly have been written anywhere other than the land of Israel:

These are the things that have no measure: The Pe’ah of the field, the first-fruits, the appearance [at the Temple in Jerusalem on Pilgrimage Festivals], acts of kindness, and the study of the Torah.

If you recall, the custom of agricultural charity was central to the biblical book of Ruth, and appears in the Torah. So, here you have a beautiful example of multi-century continuity of text and customs related to the land of Israel: from the Torah, to the book of Ruth, and to the Mishnah.

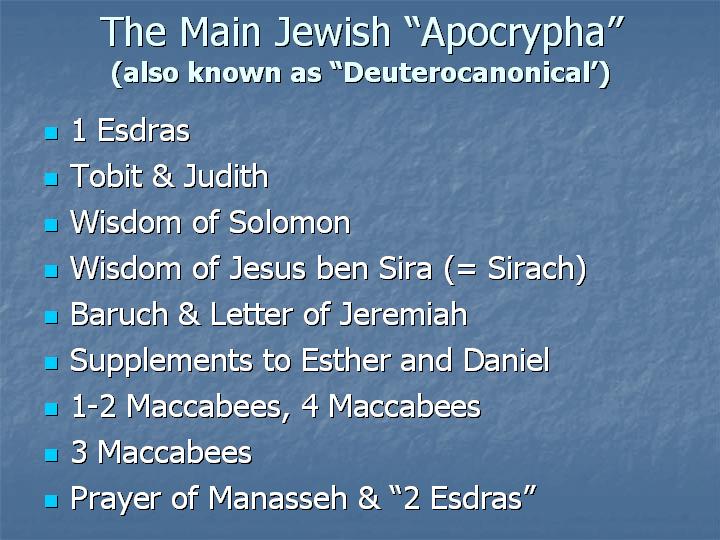

But even this is just the tip of the vast continuous textline originating in the land of Israel. I already discussed in a previous post, the four books of Maccabees, which fill in an important piece of the puzzle around the formation of the Hasmonean dynasty. Besides the books of Maccabees, there are actually dozens of other Jewish books, mostly written in Hebrew originally, which were not included in the Jewish biblical canon, but have nevertheless been preserved in Greek or other translations.

You can read the full text of many of them at earlyjewishwritings.com . What’s more, fragments of many of these books were found alongside copies of the Bible as part of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and are now digitized. Although many of these books give slight variations of the narratives of the biblical traditions, not a single one of them presents a completely different narrative of the formation of the Jewish people in the land of Israel. Given the vastness of the textual material that has been recovered, it is hard to believe that there were other formative myths circulating amongst Second Temple Jews which did not get written down. Based on the Dead Sea Scrolls, we can be quite confident that Second Temple Jews believed in the biblical narrative of how the Jews came to live in the land of Israel. So, even if some archeologists claim that the early Bible is pure fiction, the fact that the Jews in the land of Israel all believed and documented these stories over 2,000 years ago is a stronger and more ancient basis for national identity than any other nation can claim.

From Mishnah to Talmud(s)

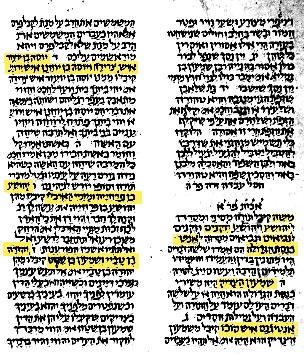

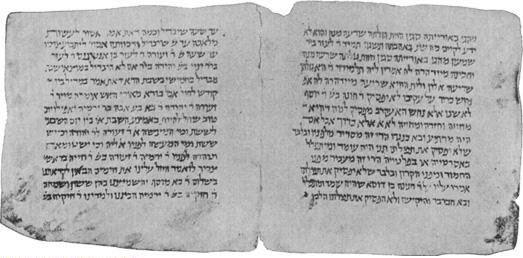

The next link in the textual chain after the Mishnah is the Talmud. There exist, not one, but two Talmuds: the Bavli (Babylonian) Talmud (which most people know) and the Yerushalmi (Jerusalem) Talmud. In the three centuries following the redaction of the Mishnah, rabbis throughout Israel and Babylonia analyzed, debated, and discussed that work. These discussions form the Gemara (גמרא). Gemara means “completion” (from the Hebrew gamar גמר: “to complete”) or “learning” ( from the Aramaic: “to study”). Fragments of the Jerusalem Talmud, dating back to the 9th century CE, were found in the Cairo Geniza.

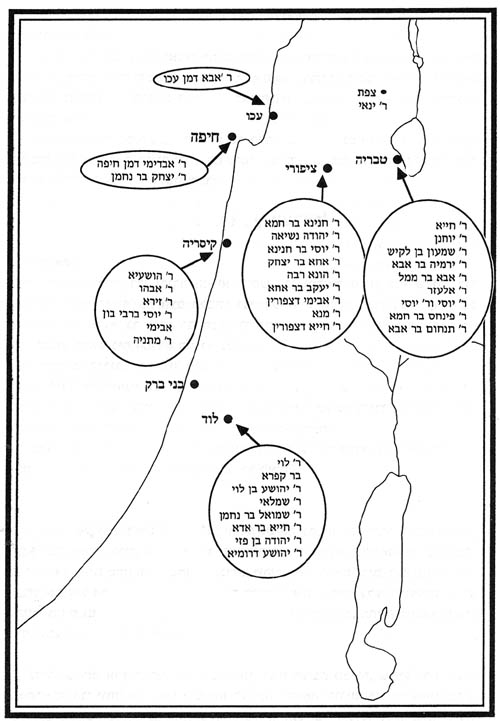

The Jerusalem Talmud includes the (almost) identical text of the Mishnah as in the Babylonian, along with the written discussions of generations of rabbis in the Land of Israel (primarily in the academies of Tiberias and Caesarea) which was compiled c. 350-400 CE.

One of the most illuminating aspects of the Jerusalem Talmud are the stories (Agadot) about Babylonian Rabbis, like Rabbi Zeira, who came to the land of Israel and had difficulty adjusting to the different local customs. His first words upon arriving in Israel were: “The air of Israel makes one wise.” But subsequent texts depict some harsh encounters. For example, in Shir HaShirim Raba, an Israeli Midrash from the same period, there is a story about Rabbi Zeira going to the Jerusalem market and asking a vendor to “weigh fairly”. The vendor gets very angry at him and yells back: “Babylonian, get out of here!”. Evidently, the Jerusalem vendor did not appreciate his insinuation that he may be cheating with his scales.

The Jerusalem Talmud and the late Midrashic texts demonstrate that even though the land of Israel was

occupied first by the Greeks and then by the Romans, Jewish creative output continued in full force, and both religious as well as secular customs were recorded in the vast textual output of the Amoraim and later sages. The following map shows the major Yeshiva centers in Roman times, and the lineage of sages whose teachings are included in the Jerusalem Talmud and late Midrashim.

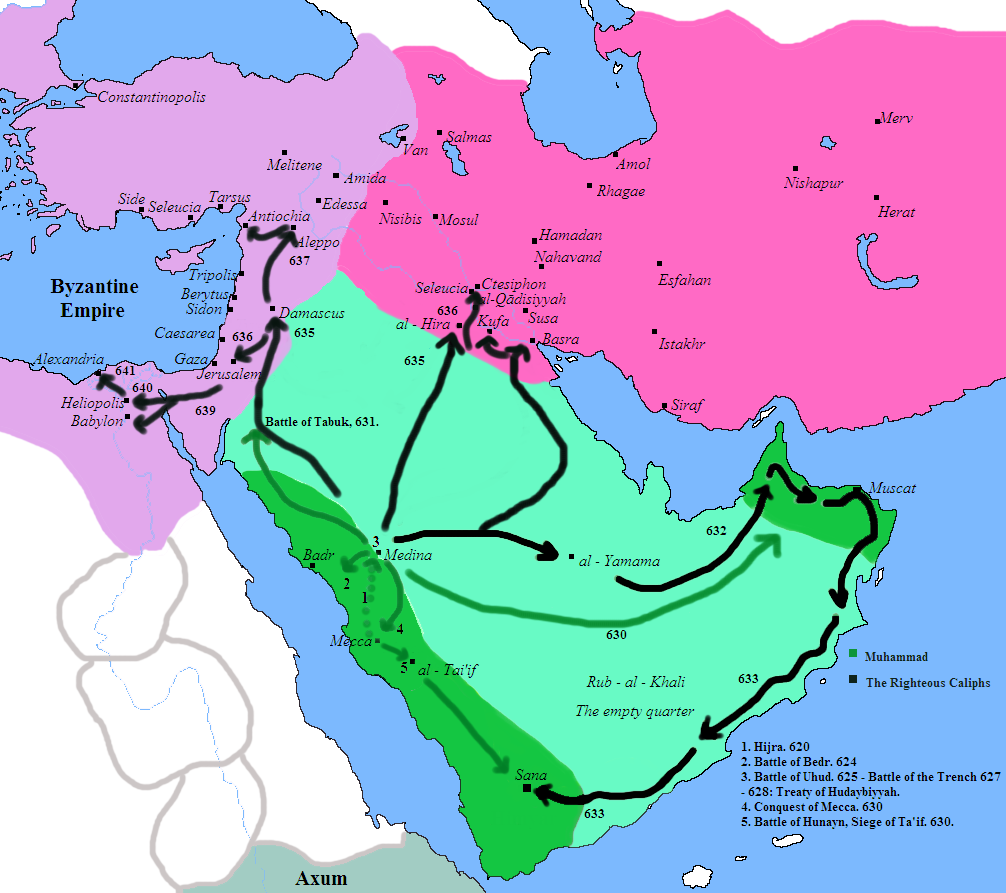

The Arab Invasion

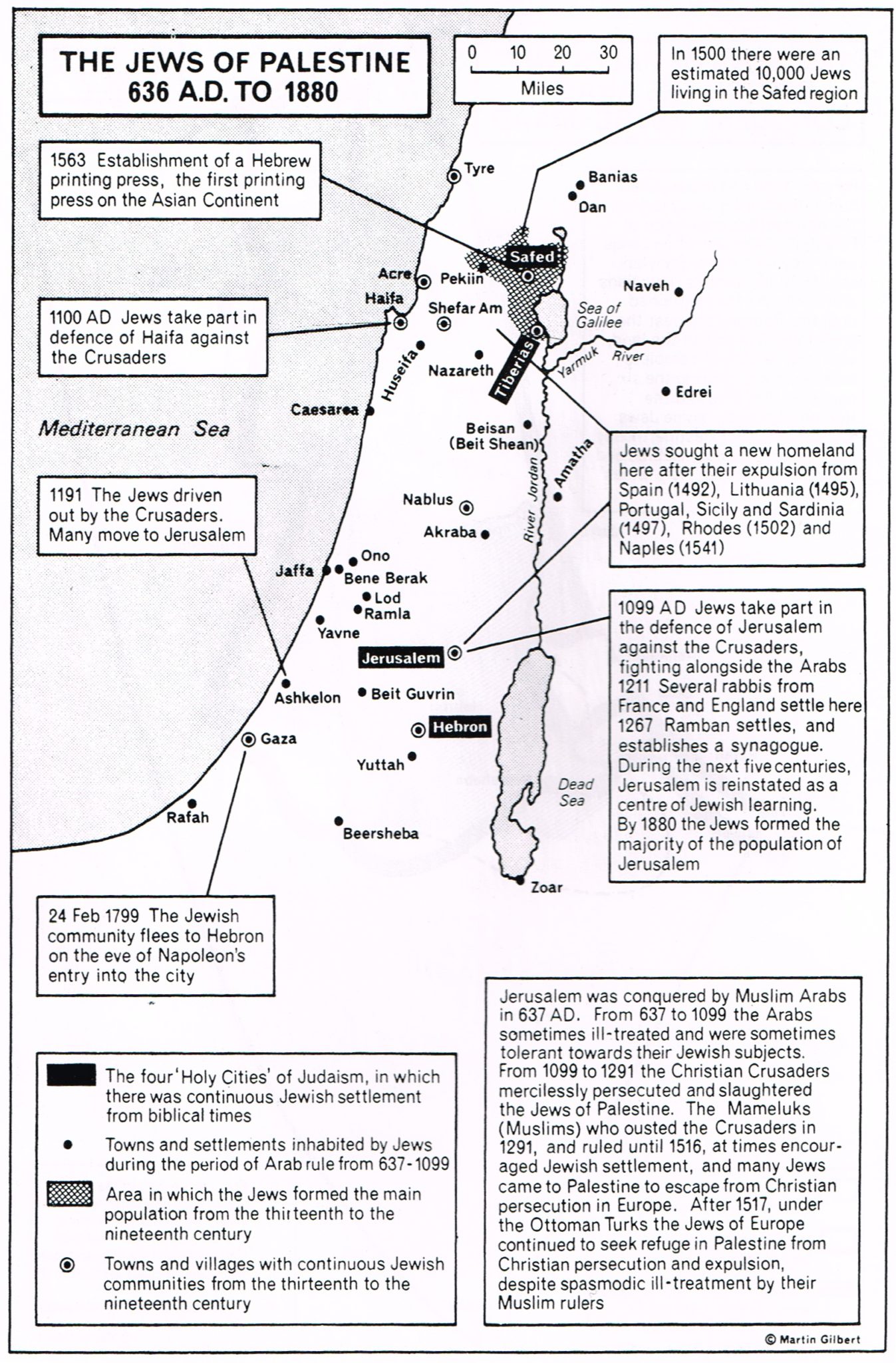

The Arab Muslim conquest, starting in 636 CE, was the most devastating blow to Jewish continuity in the land of Israel.

Some historians, such as Ben-Zion Dinur, consider this event much more significant than the destruction of the Second Temple. Dinur’s book Israel and the Diaspora begins the diaspora timeline with the Arab conquest and ends with the Jewish Zionist revival in the 19th century. In his view, the real diaspora lasted roughly 1,200 years, from the 7th century to the 19th century.

Dinur compares the Muslim invasion of Israel in 636 CE to the Muslim invasion of Spain, which took 800 years for the Spanish people to reconquer from the Muslim invaders. In both cases, the land was eventually returned to its rightful owners, although in the case of Israel it took 400 years longer, due to the rise of an even stronger invader: the Ottoman Empire.

However you look at the Muslim, Crusader, Mamluk, and Ottoman invaders, Jewish textual continuity in the land of Israel did not end with the Jerusalem Talmud. There are scores of texts and Midrashic works that were composed in Israel during these centuries.

One example, which is dated to the 8th or 9th century, is Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer, which has references to Muslim traditions, like mixing in the name Fatimah (daughter of Muhammad) into a Midrash about Abraham and Ishmael:

THE TRIALS OF ABRAHAM 219

…When Ishmael came (home) his wife told him the story. A son of a wise man is like half a wise man. Ishmael understood. His mother sent and took for him a wife from her father’s house, and her name was Fatimah.-

Commentaries on Mishnah and Talmud

The next layer in the Jewish textline are the commentaries. You are probably familiar with the Rashi commentary on the Bible, but Rashi also wrote an indispensible commentary on the Babylonian Talmud (which appears in every modern version), and dozens of other commentators helped interpret and decipher the Jerusalem Talmud. This site contains hundreds of Hebrew commentaries (Perush, Seforim) on the Jerusalem Talmud from medieval to current periods.

The period of the turn of the first Millennium in the land of Israel, even before the brutality and destruction of the crusades was marked by many disasters. Famine struck the land, there were revolts by Arab tribes who took over Jerusalem and Ramle and imposed high taxes in 1024, and in 1034 there was a devastating earthquake.

The head of the Yeshiva in Jerusalem and the leader of the Jewish population was for the years 1025-1051 was Shlomo Ben Yehuda followed by Daniel Ben Azariah. Some of their writings were found in the Cairo Geniza.

The Preservation of the Hebrew Language

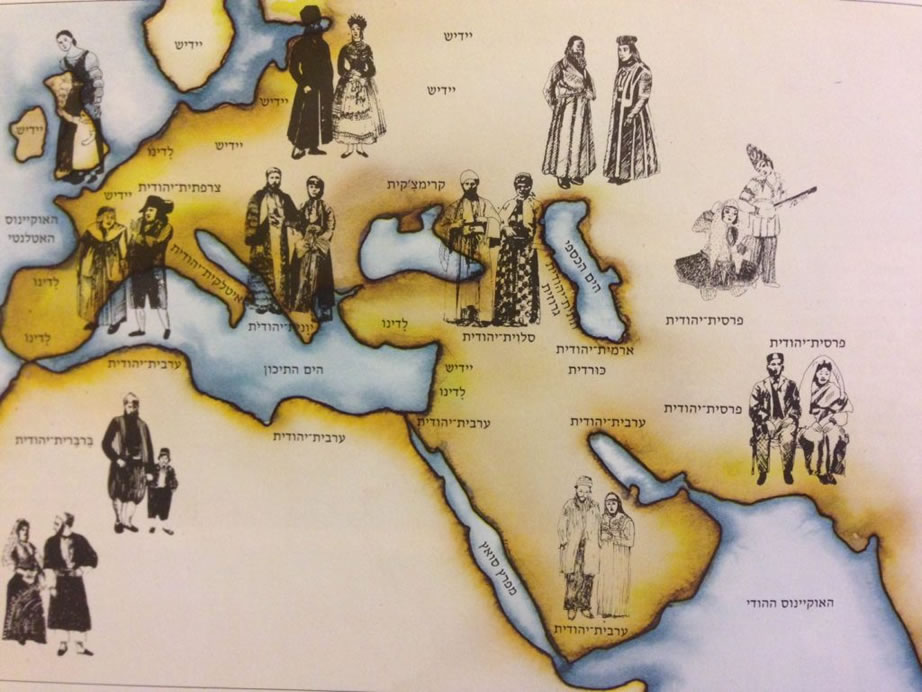

The preservation of the Hebrew language is one of the big mysteries of the Jewish textline. How was the ancient language preserved so faithfully through centuries of dispersion with enough proficiency to create new texts? Think about it. If you grew up in America and learned “Bar Mitzvah Hebrew” – would that be enough to create a major new text in Hebrew that would be studied for centuries? Besides endless commitment, it also requires a circle of people who can proof read, understand, copy and transmit the new text. One way the Jewish people kept up their Hebrew proficiency was to read and write their host country languages in Hebrew script. You probably know about Aramaic, Yiddish and Ladino, but there are also many variants of Judeo-Arabic languages and others.

One unique medieval Hebrew text that originated in Yemen around the year 1340 is Midrash HaGadol which modern scholars almost uniformly attribute to Rabbi David Adani, the leader of the Jews of Aden. The Jews of Aden were such avid bibliophiles that the Egyptian India traveler Ḥalfon b. Nethanel went there for books that he could not get elsewhere. Many of the most important Hebrew literary creations, such as the poems of Judah Halevi and Moses ibn Ezra, have been preserved in manuscripts found in Yemen. The Midrash HaGadol of David Adani shows that he possessed an exceptionally rich, specialized Hebrew library, containing works that have not yet been found in their entirety elsewhere.

The Development of The Hebrew Vowel System

It is important to understand that the Hebrew language was not just in “maintenance mode” for the entire period of the Jewish exile. Even though the language was not actively spoken in daily life, there were some important innovations that were introduced into it over the centuries. The most important innovation was the system of vowels known as niqqud (ניקוד). Anyone who has studied Hebrew knows that the vowels are expressed using a system of dots and lines under and inside the Hebrew letters, and this is crucial to knowing how to correctly pronounce every Hebrew word. When you study a Torah portion, for example, you usually study it with the vowels first, but then, when it’s time to read from the actual Torah scroll, you find that there are no vowels in that. Why is that? Because the vowels were introduced much later.

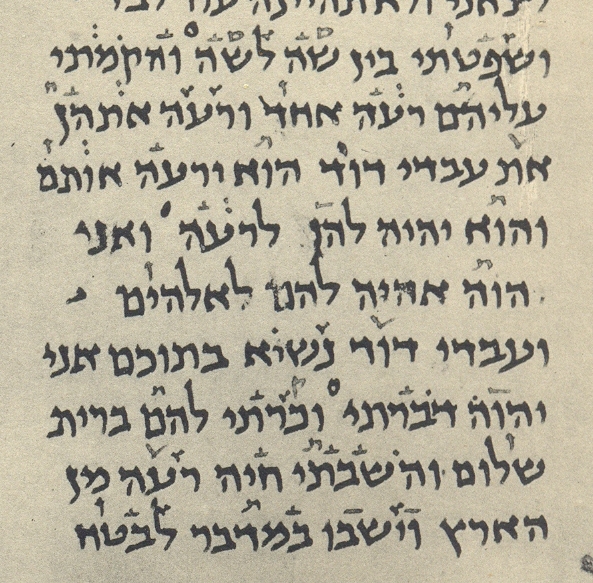

Originally, there was a system called Babylonian niqqud in which the dots and lines were displayed above the text as shown below. This system was popular in the 7th, 8th and the beginning of the 9th century.

However, during the 9th and 10th century, in Tiberias (in the land of Israel), a new system of vocalization became popular: the Tiberian niqqud.

Tiberias was the capital of the Muslim regime in northern Eretz-Israel, and the most important economic center in the country. Its main commercial ties were with Syria to the north and with Baghdad and Persia to the east. Agricultural exports from Eretz-Israel in the tenth century included olive oil, raisins, and carobs, as well as cotton and textiles, and Tiberias was known for the manufacture of textiles and m

ats. The Jewish market in Tiberias was large and varied, and it was known for its low prices. Tiberias flourished until the arrival of the Crusaders in the twelfth century. The city was destroyed during the Crusader wars and remained in ruins until it was rebuilt in the sixteenth century.

One of the most important projects connected with the name of the city of Tiberias was the creation of vocalization and cantillation marks and the preservation of the text of the Bible by means of the Masoretic commentaries. Rabbi Avraham Ibn ‘Ezra wrote in his book, Tsachut (Correctness) that “the Sages of Tiberias are the main ones, for from them came the Masoret, and we received vocalization from them”. It was said to be handed down orally for generations, and was used to write one of the most important copies of the Bible called the Allepo Codex. This was the actual copy of the Bible which Maimonides is believed to have used to derive his teachings.

The system of Tiberian Hebrew vocalization, which is still in use today, is further proof that the Jewish textline continued to be developed and expanded in the land of Israel even after the center of Jewish learning had moved to Babylon and later to Spain and Europe. Israel was always the epicenter of the Hebrew language.

Medieval Israeli Geography and Halacha

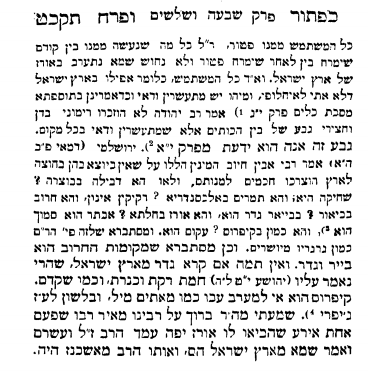

In 1322, Rabbi Ishtori Haparchi wrote the first Hebrew book on the geography of the land of Israel: Sefer Kaftor Vaferech (Hebrew: ספר כפתור ופרח (literally “Button and Flower”). In this book, Haparchi lists the names of towns and villages in Israel and discusses the topography of land based on first-hand visits to the sites and the Rabbis that lived in each town. Modern scholarship has determined that most of the 180 ancient sites he identified were correct, among them Usha, Modi’in, Betar, Mount Meron, Shiloh and Akko. In the following excerpt, he explains that Cyprus is an island 200 miles off the coast of Akko:

Halperin’s Etz Chaim

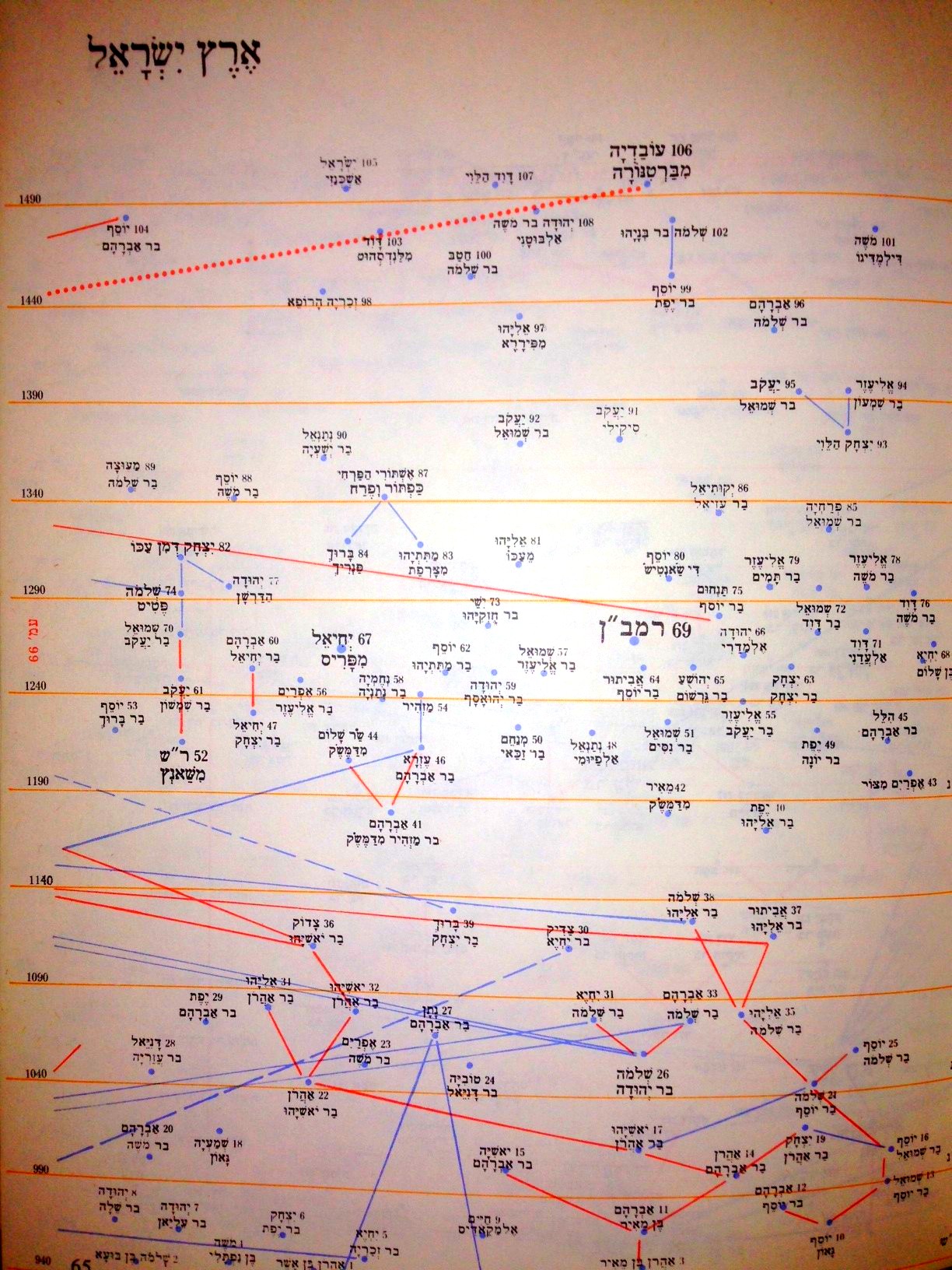

A recently deceased Rabbi by the name of Rafael Halperin (who was previously a famous wrestler in Israel), spent the later part of his life recreating the textline and the matching Rabbinic line through the middle ages. His life’s work is a Hebrew book called Etz Chaim in which he depicts graphically and in great detail the main Rabbinic family trees, migration of Yeshivas, the main Books produced in each location, and many more details that bring the Jewish textline to life. The image below is part of the graph of Rabbinic continuity in the land of Israel (bottom to top: between the years 940 to 1490). In the center is the great Ramban (רמב”ן Nachmanides):

Print It!

The first print edition of the Jerusalem Talmud appeared in 1523 in Venice, Italy, which marked a new era of mass-produced Jewish books rather than the hand-copied versions that existed until then:

After the Expulsion from Spain

The same period also saw a huge revival in textual output of the city of Safed in Israel. There is a long list of important sages in Safed who continued the textline. The most famous is:

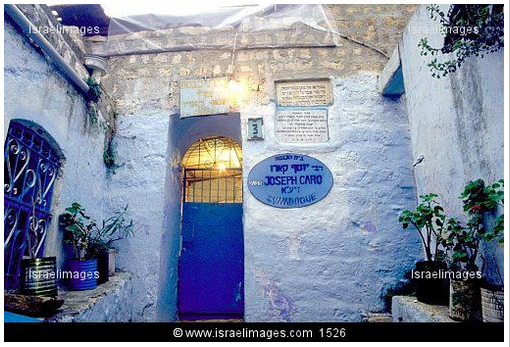

Rabbi Yosef Caro (1488-1575):

Codifier and Kabbalist, student of Rabbis Yaakov Beirav and Shlomo Al-Kabets, chief rabbi of Zefat from 1546. Author of several major works, including the Shulchan Aruch (“The Prepared Table”–Code of Jewish Law), a compendium of the laws of the Torah governing a Jew’s entire life: personal, social, family, business, and religious. Notwithstanding subsequent revisions, it remains the foremost authoritative work on Jewish law and practice and is universally accepted by Jews the world over.

There were also a multitude of famous Kabbalists that earned Safed the name City of Kabbalah.

Tiberias was another important center for Jewish textual creativity, as witnessed by the fact that Maimonides Tomb is located there.

Maimonides was a 12th-century Sephardi Jewish legal expert, scholar, philosopher and doctor and one of the greatest minds ever produced by the Jewish people. His most comprehensive work on Jewish law was the 14-volume Mishne Torah, considered a work of genius. Written on the wall of his strange, metal-topped shrine in Tiberias is a saying coined by his contemporaries: “From Moses to Moses, there has never been another Moses” — a reference to the biblical lawgiver Moses.

Other Texts Connected to Israel

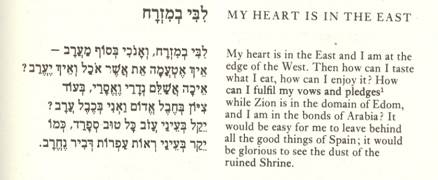

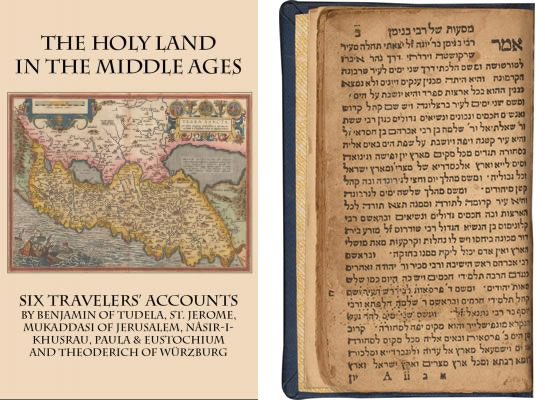

Of course, there are so many other Jewish texts that demonstrate the continuous connection of the Jews to the land of Israel. These include the texts of the daily Jewish prayers for ingathering in Jerusalem (including the custom of praying towards Jerusalem), the Israel-longing poetry of medieval Spanish Jews like Yehuda Halevi (shown above), the Hebrew travel logs of Benjamin of Tudela from 1165, and the vast literary output of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews in Europe, which is a whole topic onto itself.

Of course, there are so many other Jewish texts that demonstrate the continuous connection of the Jews to the land of Israel. These include the texts of the daily Jewish prayers for ingathering in Jerusalem (including the custom of praying towards Jerusalem), the Israel-longing poetry of medieval Spanish Jews like Yehuda Halevi (shown above), the Hebrew travel logs of Benjamin of Tudela from 1165, and the vast literary output of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews in Europe, which is a whole topic onto itself.

One example of a famous 16th century European Rabbi who was intimately connected to Rabbis in Israel was Moses Isserlis of Krakow, Poland. He expanded on the work of Rabbi Yosef Caro (mentioned above) of Safed to produce a version of the Shulchan Aruch that had Isserlis’ commentary embedded on the same page. This was the first time the entire range of Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions were merged in one Hebrew book.

The Textline is Growing!

With so much online information at our fingertips today, it is easier than ever to follow the continuous textline that has bound the Jewish people to the land of Israel from time immemorial. Every Jewish generation since biblical days has taken the time to study and debate the Jewish texts that preceded it, and contribute to the ever-growing literary legacy. Some interpreted, some elaborated, some disagreed, some refuted, and some took the tradition in new directions.

In recent decades, 13 Jewish authors have won the Nobel prize i n literature, among them one Israeli (S.Y. Agnon).

n literature, among them one Israeli (S.Y. Agnon).

Since 1948, the literary output of Israel has soared. Today, Israel is number one in the world in yearly per-capita publication of new books, most of them in Hebrew, the exact same language that was used to write the Bible and most Jewish texts in between. The Jewish textline marches on.