Make Your Notes Bounce

Dan Adler August 2002

Great musicians of all disciplines share one thing in common: their notes bounce. But, what does that mean? And how do you acquire it? This article will try to demystify this subject by isolating extreme examples of how it is done by a variety of great players in classical and jazz disciplines.

Bouncing in Time

I’m not sure if bounce is a universal term. Other people call it time feel, groove, touch, swing etc. I like the term bounce because it connotes a complete action: you hold the ball in your hand, then you throw it against the wall, it hits, and bounces back to you. If you throw it hard, it comes back faster. If the wall is soft, it may come back slower. The equivalent motion for a pianist is to hit the note and let the finger bounce back up. That defines a single note. For a guitar player, the motion is picking the note and then releasing it. Bounce is quite difficult to achieve on guitar, because the attack and the release are done by different hands, but more on that later.

Two things define bounce:

- The placement of the note in its time slot

- The duration and envelope of the note

The duration of a bouncy note is usually short. This leads some people to believe that bounce is the same as playing staccato, which is not quite true. You can play legato with bounce, but for beginners it’s much easier to concentrate on short note duration, so I recommend practicing with short notes and spaces between each note.

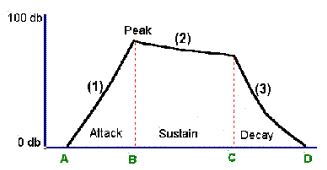

Technically, bounce is an attribute of the envelope of the sound. The envelope of each note is made up of 3 parts: Attack, Sustain and Decay. The following picture shows this as a function of time:

So, to make your notes short, all you do is make the Sustain and Decay minimal. On piano, this is achieved by simply raising your finger after you hit the note. On guitar, you also have to raise your finger, but in this case, it’s the left hand finger you have to raise to release the note and muffle it.

So, to make your notes short, all you do is make the Sustain and Decay minimal. On piano, this is achieved by simply raising your finger after you hit the note. On guitar, you also have to raise your finger, but in this case, it’s the left hand finger you have to raise to release the note and muffle it.

The next question is where does the Attack occur within the time or the pulse. Imagine the pulse (or beat or time) as a series of periodic events that occur over time:

Now, think about what the envelope of each note would look like on this axis. The notes might be longer:

Or, they might be shorter:

What would the notes look like if a guitar player simple picks each note at the right time without applying any decay in the left hand? The notes would look something like this:

In other words, the notes run into each other because the previous note is still sustaining while the next one is played. This hardly ever sounds bouncy, except in the hands of people who have already mastered bounce. So, the first key observation about bounce is:

Notes must be separated from each other by silence.

What Does Bounce Sound Like?

As I mentioned – it’s hard to explain bounce in technical terms, but it’s pretty easy to demonstrate, so I will try to demonstrate here with a number of examples in MP3 format.

One major disclaimer about these examples is that they do not necessarily represent how these artists always play. It’s not even the best of their work. I have taken some extreme examples from these artists that serve well to demonstrate the concept of bounce. Once the concept is mastered, it can be applied in ways that are much subtler that the ones shown here, and most of these artists use this concept in a more subtle way most of the time. But, if I try to demonstrate the concept to you in one of its more subtle incarnations, you will probably miss the point.

Glenn Gould

Glenn Gould is one of the best examples of how to make straight eighth or quarter notes bounce within the classical idiom. The two examples given below are from ‘The Glenn Gould Variations – The best of Glenn Gould’s Bach’ on Sony:

- BWV 829: Listen to the way the notes played by the right hand bounce.

- BWV 924: An even more extreme and slow example of bounce in the right hand notes, while the left hand notes are more legato. Listen over and over until you hear the bounce in how the notes begin and end. Notice how each note is charged with energy, excitement and, well, bounce…

If you can’t hear the bounce in Glenn Gould’s music, then you will probably not hear it in anyone else’s music either. Listen and Play along with these examples (even if you play random notes – just match the feel), or try to play any classical etude with a bounce like this. It is much easier to learn bounce in a classical context than in a jazz context, because in jazz you have the added dimension of swing accents. I recommend, even for jazz players, to first acquire the bounce feeling by playing some classical music (such as Hanon for piano or violin studies or Bach), and only apply it to jazz later.

Oscar Peterson

Oscar Peterson’s early recordings offer many examples of bounce and swing. When you compare Oscar to Glenn Gould you should notice that the bounce is very similar, but Oscar then inserts very strong accents on some notes, which is what gives it swing in addition to bounce.

- The Smudge: This is the head of one of Oscar’s famous blues tunes. Listen especially to way he plays the melody, and you should be able to hear the bounce in his notes. Any of the Oscar Peterson songbook albums offer many more examples of his swing and bounce.

Dave McKenna

Dave McKenna’s sense of bounce and swing has a lot in common with Oscar Peterson’s. The two excerpts below are from a trio album he recorded in the 50’s.

- I Should Care: This is a great example of how bounce works both on slow and fast passages. He starts slow and bouncy, and then speeds up. In the fast passages, fewer notes get accented, but the ones that do are very strong compared to the others.

- Secret Love: This is a slightly faster tempo, but you can hear each note pop out or bounce very clearly.

Clifford Brown

Clifford Brown is one of the most crystal-clear examples of how bounce and swing sound on trumpet. Each note is separated from the next one by a silence. This is what makes them bounce. When he does make notes run into each other – it’s always for a special effect, and he quickly resumes his bounce thereafter.

- A Night In Tunisia: This is a small excerpt from “A Night At Birdland” with Art Blakey. Notice especially how the notes bounce and swing when he plays a string of successive eighth notes.

Ornette Coleman

If you have not listened much to Ornette Coleman you are missing one of the best examples of swing and bounce. This is an excerpt from the “New York is Now” album.

- Garden Of Souls: This is a great example of how Ornette can make the notes bounce over one meter, and then at some point he leads the group into a double time feel. Listen to the switchover several times, and notice that Ornette is the one who defines the new feel by making the notes bounce differently and the rest of the group picks up on it instantly.

Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins is a great example of swing and bounce. This is a very early recording live at the Village Vanguard in 1957 with just bass and drums (Elvin Jones).

George Benson

- California Dreaming: This may not be one of George Benson’s best-known recordings, but it’s one that most clearly demonstrates how he can make the notes bounce. From the first note, you can feel the energy in each note, the same way you can feel it in Glenn Gould’s notes.