As I mentioned in a previous blog, the four books of Maccabees do not mention the miracle which we celebrate as the main theme of Hanukkah: The oil canister that lasted eight days.

In 1 Maccabees Chapter 4, the eight days of Hanukkah are said to begin on the 25th of Kislev (as we currently celebrate it), and the reason given for the eight day period of celebration is that the Maccabees celebrated “the dedication of the altar eight days”. So, חנוכת המזבח, as it appears in the song Maoz Tsur is given as the main reason for the holiday.

52] Now on the five and twentieth day of the ninth month, which is called the month Casleu, in the hundred forty and eighth year, they rose up betimes in the morning,

[53] And offered sacrifice according to the law upon the new altar of burnt offerings, which they had made.

[54] Look, at what time and what day the heathen had profaned it, even in that was it dedicated with songs, and citherns, and harps, and cymbals.

[55] Then all the people fell upon their faces, worshipping and praising the God of heaven, who had given them good success.

[56] And so they kept the dedication of the altar eight days and offered burnt offerings with gladness, and sacrificed the sacrifice of deliverance and praise.

[57] They decked also the forefront of the temple with crowns of gold, and with shields; and the gates and the chambers they renewed, and hanged doors upon them.

[58] Thus was there very great gladness among the people, for that the reproach of the heathen was put away.

[59] Moreover Judas and his brethren with the whole congregation of Israel ordained, that the days of the dedication of the altar should be kept in their season from year to year by the space of eight days, from the five and twentieth day of the month Casleu, with mirth and gladness.

In 2 Maccabees Chapter 10, the same date of 25th of Kislev is specified, but a different reason for the eight days is given: “as in the feast of the tabernacles”, which means the length of the Holiday was designed to match Sukkot:

[5] Now upon the same day that the strangers profaned the temple, on the very same day it was cleansed again, even the five and twentieth day of the same month, which is Casleu.

[6] And they kept the eight days with gladness, as in the feast of the tabernacles, remembering that not long afore they had held the feast of the tabernacles, when as they wandered in the mountains and dens like beasts.

[7] Therefore they bare branches, and fair boughs, and palms also, and sang psalms unto him that had given them good success in cleansing his place.

[8] They ordained also by a common statute and decree, That every year those days should be kept of the whole nation of the Jews.

Dr. Binyamin Lau in the first volume of his book Sages posits that our sages, living in Ere

tz Israel after the failed Bar Kochba revolt, “oil-washed” the Maccabean revolt story to avoid upsetting the Romans. They realized that a holiday that celebrates Jewish independence through military struggle would not go over well with the Romans.

As a result, the Mishnah does not contain a Hanukkah tractate. Its celebration is assumed, but not mandated or explained, which could hardly be an oversight.

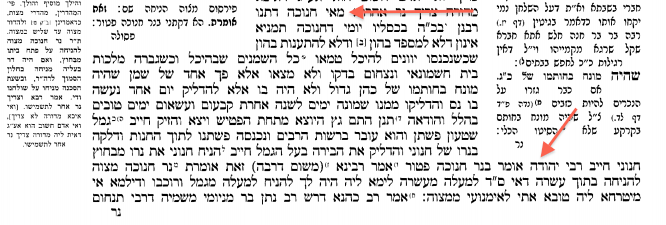

The source of the Hanukkah Miracle tradition is one paragraph in Shabbat 21b:

What is [the reason of] Hanukkah? For our Rabbis taught: On the twenty-fifth of Kislev [commence] the days of Hanukkah, which are eight on which a lamentation for the dead and fasting are forbidden.

For when the Greeks entered the Temple, they defiled all the oils therein, and when the Hasmonean dynasty prevailed against and defeated them, they made search and found only one cruse of oil which lay with the seal of the High Priest, but which contained sufficient for one day’s lighting only; yet a miracle was wrought therein and they lit [the lamp] therewith for eight days. The following year these [days] were appointed a Festival with [the recital of] Hallel and thanksgiving.

Based on this, the specific issue was that the Greeks defiled all the oil canisters by breaking the seal of the High Priest which sanctified it. Only one can had the seal intact, making it fit for worship, and the miracle was that it lasted for eight days.

Since this appears in the Gemara section of the Talmud without attribution, we can reasonably assume that it was added by the sages of Babylon hundreds of years after the Maccabean revolt, probably during late Roman times.

So, how do we know that Hanukkah was celebrated in the land of Israel in the 1st or 2nd century C.E.?

The answer is actually in the next paragraph of the same tractate (see second red arrow above), where a seemingly unrelated issue is discussed: when a camel carrying silk passes by an outdoor candle and the silk catches fire, who is liable?

Rabbi Judah (who lived in the 2nd century C.E.) answers that the land owner is not liable if it happened on Hanukkah, from which we can deduce that the camel owner should have expected candles to be burning on Hanukkah, and that means Hanukkah was already celebrating at that time.

We learnt elsewhere: If a spark which flies from the anvil goes forth and causes damage, he [the smith] is liable. If a camel laden with flax passes through a street, and the flax overflows into a shop, catches fire at the shopkeeper’s lamp, and sets the building alight, the camel owner is liable; but if the shopkeeper placed the light outside, the shopkeeper is liable. Rabbi Judah said: In the case of a Hanukkah lamp he is exempt.

The reference to “elsewhere” above is most likely to Baba Kamma 22a, where the same discussion is repeated:

Come and hear: A camel laden with flax passes through a public thoroughfare. The flax enters a shop, catches fire by coming in contact with the shopkeeper’s candle and sets alight the whole building. The owner of the camel is then liable. If, however, the shopkeeper left his candle outside [his shop], he is liable. Rabbi Judah says: In the case of a Hanukkah candle the shopkeeper would always be quit.

Here, once again, we see that Rabbi Judah makes the argument that the camel owner should expect to find burning candles being lit outside homes and stores during the eight days of Hanukkah. If the law is based on the this expectation, and we can trace Rabbi Judah to the 2nd century C.E., then we can deduce that the tradition was widespread enough at that time, and every Jew was expected to know it.

There is one more piece of evidence to strengthen the claim that the Sages “oiled down” Hanukkah to avoid provoking the Romans, and that is the story of the celebration of “Nicanor Day”. Looking back at 1 Maccabees Chapter 7, we can find the background for the celebration:

[26] Then the king sent Nicanor, one of his honorable princes, a man that bare deadly hate unto Israel, with commandment to destroy the people.

[27] So Nicanor came to Jerusalem with a great force; and sent unto Judas and his brethren deceitfully with friendly words, saying,

[28] Let there be no battle between me and you; I will come with a few men, that I may see you in peace.

[29] He came therefore to Judas, and they saluted one another peaceably. Howbeit the enemies were prepared to take away Judas by violence.

[30] Which thing after it was known to Judas, to wit, that he came unto him with deceit, he was sore afraid of him, and would see his face no more.

[31] Nicanor also, when he saw that his counsel was discovered, went out to fight against Judas beside Capharsalama:

After Nicanor failed to trick Judas into an ambush, a battle ensues in which Nicanor was defeated and killed. The day was designated as “Nicanor Day”:

[49] Moreover they ordained to keep yearly this day, being the thirteenth of Adar.

But, wait…doesn’t the 13th of Adar sound familiar? That is one day before Purim. At this point, the Hanukkah story has a strange entanglement with the Purim story: the 13th day of Adar is designated as a celebration of the triumph over Nicanor (Yom Nicanor in Megillat Taanit). However, after the destruction of the Second Temple, Nicanor Day was cancelled and replaced by Taanit Esther, lending further credence to the theory that the sages were determined to blur out any celebration of Maccabee victories to avoid provoking the Romans.

For a more detailed analysis of the ancient sources of Taanit Esther, please refer to Mitchell First’s blog.