Hello everybody, my name is Dan Adler and I’d like to welcome you to Episode 8) of Active Listening in Jazz.

In this series we’ve been talking about elements of Jazz and how can you recognize them. And I want to give you a little bit of motivation now. When Jazz musicians are asked to explain what they are doing, very often they will give the analogy of storytelling. They are telling a story.

The first thing I’m going to reference is a book that I’ve been reading lately. It’s called Story Smart by Kendall Haven.

And Kendall Haven has analysed thousands of stories and has analysed audience responses to stories.

And he has analysed a set of elements which are more likely to keep your attention during a storytelling session and to memorable to you.

One of those elements ~ the first and most important element is that our brain needs to make sense of stories that we hear.

Let’s list to Kendall Haven explain that important point.

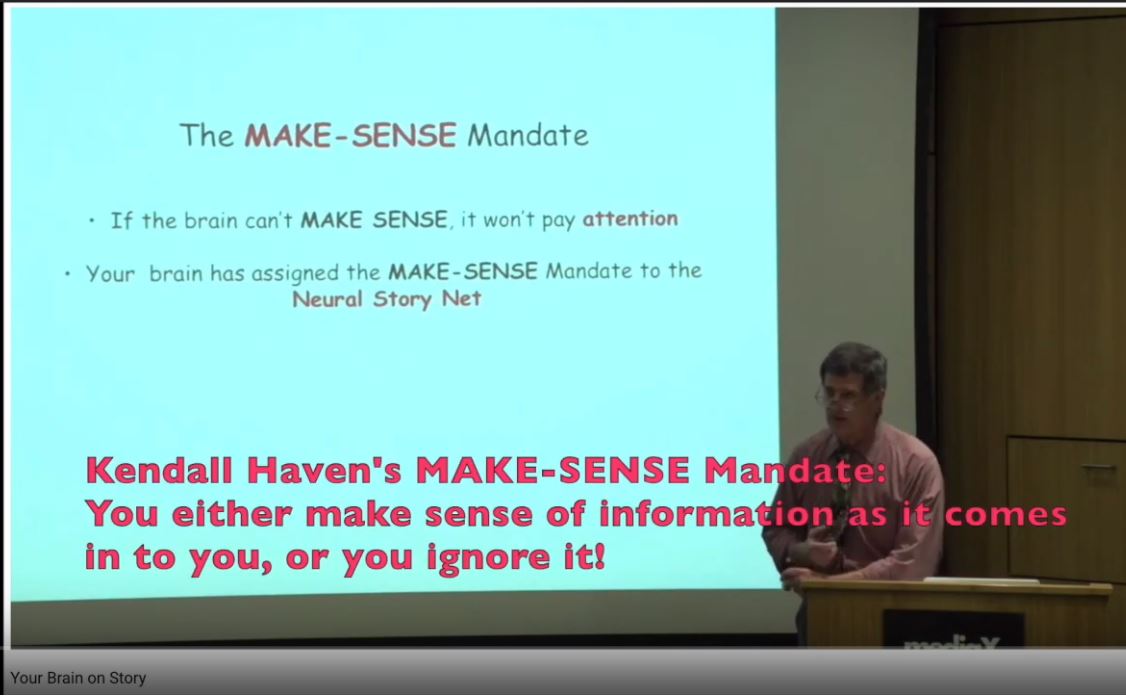

“What we’re able to show, to take from other people’s work actually, developmental psychologists work is this concept of the make sense mandate.

Either you make sense of information as it comes to you or you ignore it.”

If you are listening to Jazz and you can’t make sense out of it at all, then you are going to ignore it.

So now we are going to talk about one of the most important building blocks about Jazz and that is the idea of a musical motif.

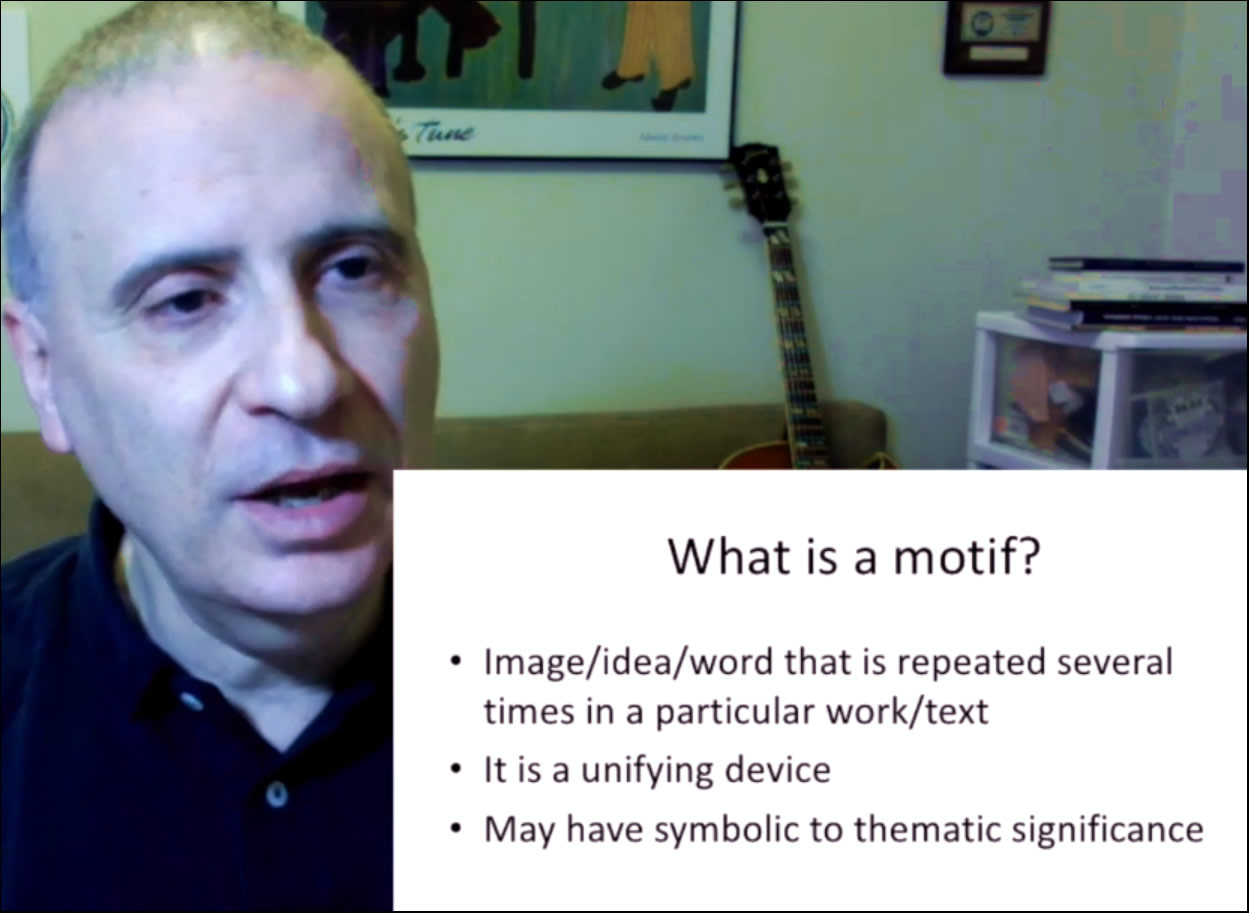

And one of the definitions of a musical motif is more generic. Doesn’t apply just to Jazz, Doesn’t just apply to music.

It’s a general idea that you have … An image, an idea.

It could be a musical idea or a linguistic idea or a word. Or something that is repeated several times in a particular work or text.

In our case we’re talking about a Jazz solo. And it is a unifying device that helps you put things together and helps you connect to the different parts that you are listening to. And it may have symbolic or thematic significance.

Meaning it may actually be something that is being developed or is a significant part of the story that is being told to you.

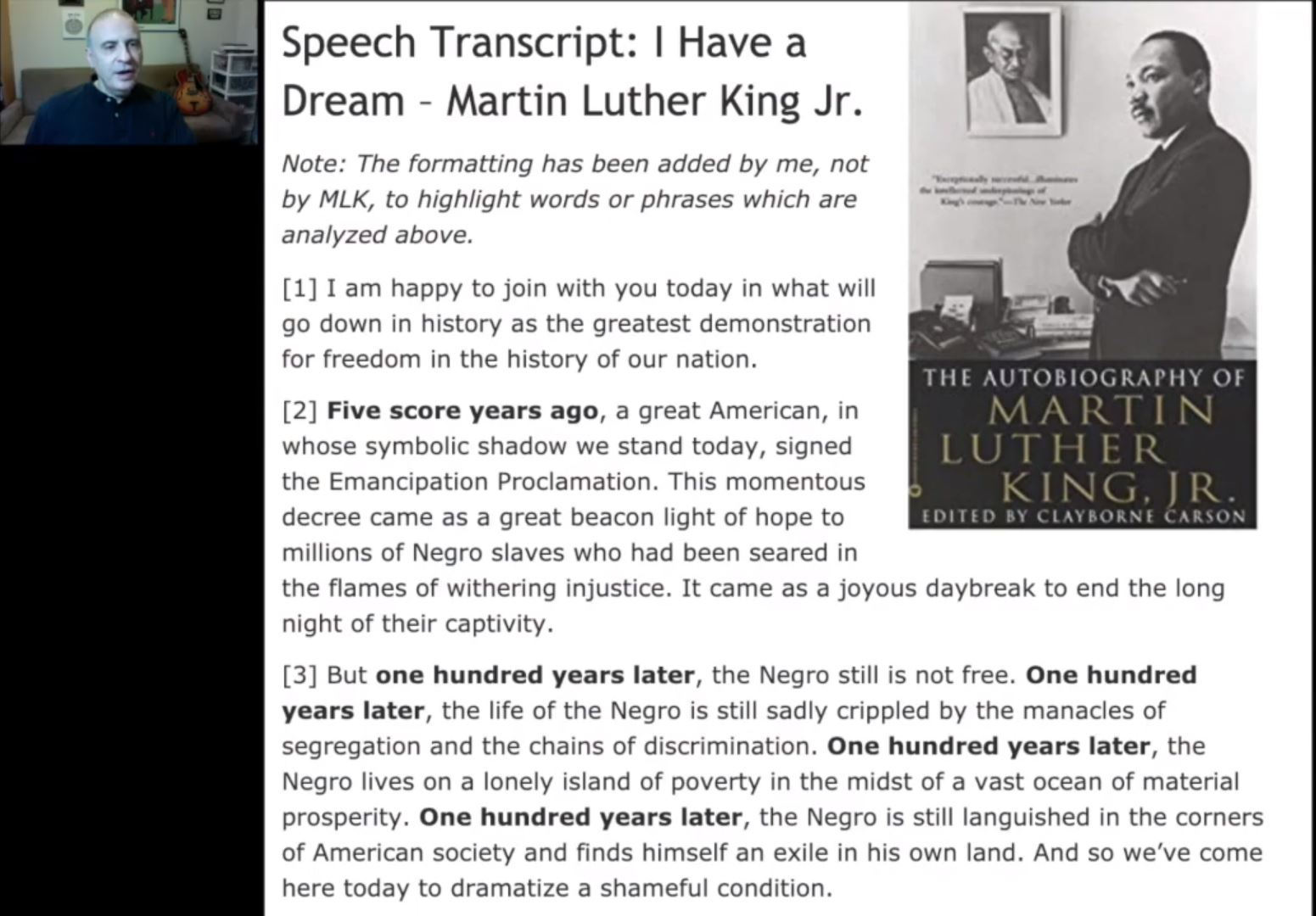

So let me start with one non-musical example and we’ll look at one of the most famous speeches in history: Martin Luther King‘s ‘I have a dream‘ speech.

And let’s look at how he used recurring techniques to give structure to different sections of the speech and make it flow.

So he starts with ‘Five score years ago‘ and continues to talk about ‘a hundred years later‘ … ‘a hundred years later‘ … ‘a hundred years later‘

~ and then:

‘Now is the time’ … ‘Now is the time’ … … ‘Now is the time‘…

~ and then another motif around:

… ‘we must‘ … ‘we must‘ … ‘we must‘

~ and then:

‘we can never be satisfied‘ … ‘we can never be satisfied‘ …

‘we have to go back to‘ … ‘go back‘

and of course ..

‘I have a dream‘ … ‘I have a dream‘ … ‘I have a dream‘ …

and then it finally ends with:

‘Let freedom ring‘ … ‘Let freedom ring‘ … ‘Let freedom ring‘ …

So a musical motif can be as simple as one note and we’ll look at one example which is a very famous song by Antônio Carlos Jobim which is ‘One Note Samba’.

In the first part of this song he takes one single note and just puts it with a rhythmic

idea. ‘ta, ta, ta, ta, ta, ta, ta, ta, ta, ta‘

“This is just a little samba built upon a single note. Other notes are bound to follow, but the root is still that note.

Now this new one is the consequence of the one we’ve just been through.

As I’m bound to be the unavoidable consequence of you.”

And this same idea carries over to Jazz soloing. Sometimes Jazz musicians will take a little germ of a musical idea ~ a motif. And keep developing it. Morphing it. Repeating it.

So let’s look at a musical motif that has become so famous it has its own Wikipedia page and its own Facebook page.

It’s called The Lick and goes:

‘Doo Ba Di Bee Dwee Do Dahh‘

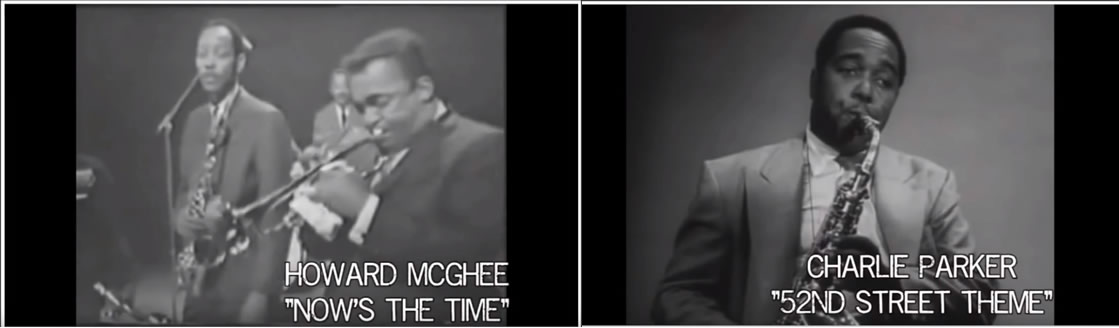

Here’s another very famous phrase. This one comes from the theme of Charlie Parker‘s Cool Blues.

Not all motifs are repetitions of well known licks or phrases. Sometimes it could just be an idea and developing

that idea.

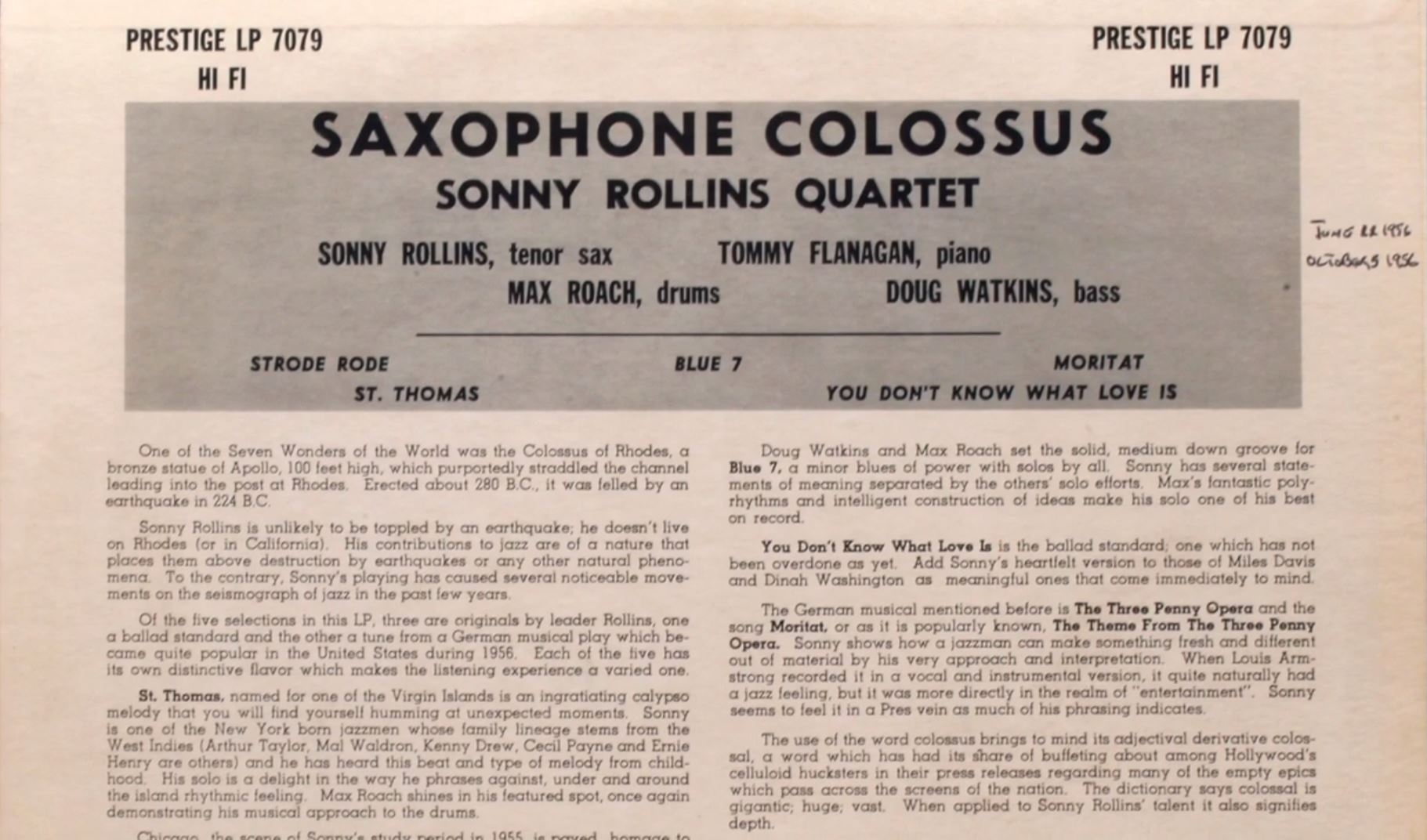

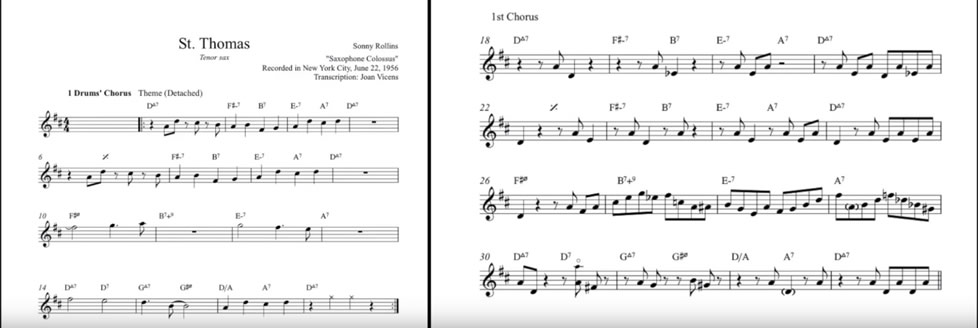

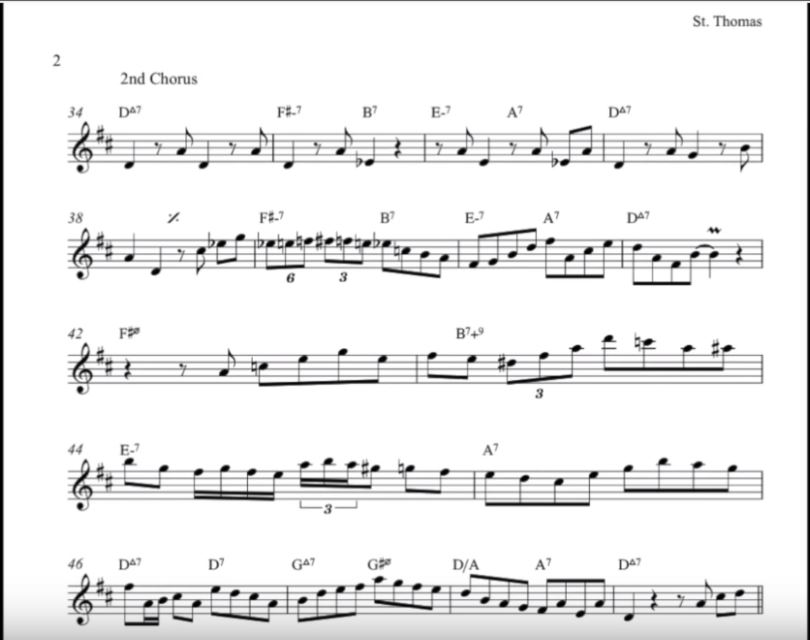

So let’s listen to the way Sonny Rollins opens the solo on one of his great tunes ‘St Thomas‘. And on this tune he starts with a two note idea.

He goes ‘ta dah … ta dah‘ … then he changes it a little bit … ‘ta dah‘.

Then he moves it a little bit rhythmically and then he repeats it twice … ‘ta dah … ta dah‘.

And then you can see how he develops that and keeps that going for about two choruses until he had enough of this idea and starts to develop new ideas.

Even without following the musical notation on that I’m sure you’re able to hear that motif and the way it was developed by Sonny Rollins.

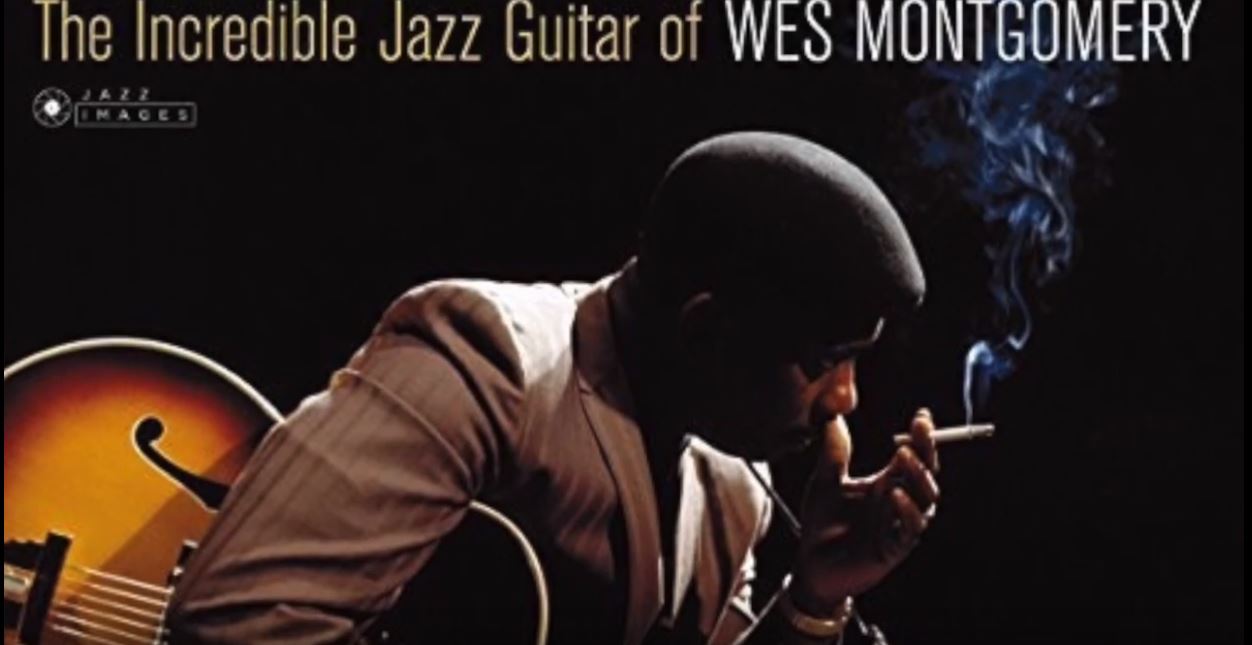

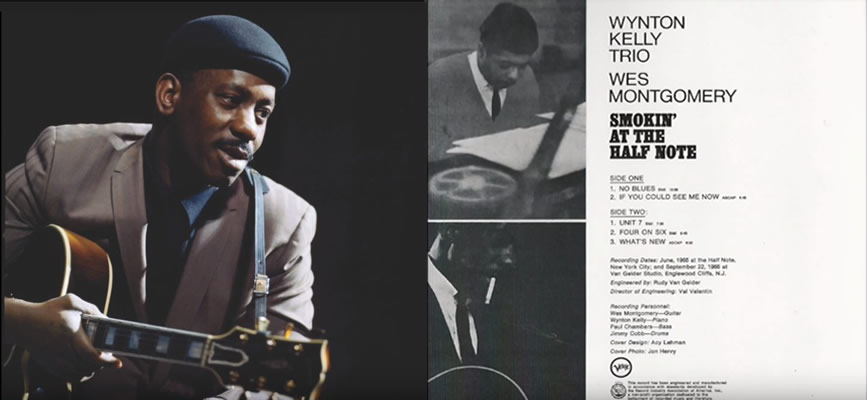

And now let’s listen to another one of my favorite players, Wes Montgomery who was also great at being able to take a motif and keep it going for a long period of time. And develop it in a very exciting way.

This is a Blues called ‘No Blues’ from his very famous album called ‘Smoking at The Half Note.

And check out this one chorus in which he plays one phrase for the whole Blues chorus.

And I hope you can refer back to the episode where we discussed Blues form and hear the Blues form by the rhythm section while Wes is playing this one phrase, over and over again.

In the next two Blues choruses you get to hear Wes using a new motif where he is emphasizing the second beat of every bar.

So if you count 1, 2, 3, 4 … 1, 2, 3, 4 … as we talked about in the previous episode about the rhythm section.

And he starts emphasizing the second beat using an octave that he keeps repeating and in between that second beat, of every other bar he keeps repeating phrases.

And at some point you can see the rhythm section catches on and starts to emphasize those beats together with him, until at some point he decides ‘ok, I’ve had enough of this idea. I’ve got a new idea.’ And he move right along to a new motif.

And another very popular source of Jazz motifs comes from the great American songbook. For example ‘The Surrey With a Fringe on Top‘ from the musical Oklahoma by Rodgers and Hammerstein.

So this next example is from my album ‘Back To The Bridge’ with the great Joey DeFrancesco.

And at some point I got it into my mind to play this phrase from ‘Surrey With A Fringe on Top’ and you can see that I play it for a very short period of time and then I kind of moved on.

But then something amazing happened when my solo ends Joey DeFrancesco the great organist, first of all he starts his solo by taking my last phrase and taking that as the first phrase of his solo.

But then right after that he goes back to that quote and he uses that to develop his next idea.

So I hope you’re beginning to see how a motif can be used either by a single player, sometimes passing from one player to the next.

Sometimes connecting with the rhythm section. Sometimes taking a motif from the rhythm and developing it melodically.

Sometimes taking a melodic idea and developing it rhythmically. And all of these things are things that the Active Listener is trying to stay on top of.

But sometimes the Jazz phrasing can get very fast and you might think at that point you can’t exactly stay on top of it. You can’t exactly determine what’s going on.

But here’s a great example from Jeremiah Macdonald. He took one of the fastest tunes by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie where they’re playing solos and exchanging phrases and he stages it as a ‘Jazz Dispute‘ as he calls it.

And the beautiful part of that is that it kind of gives you a framework to think that maybe there is conversation going on.

Even if I can’t exactly follow the exact musical notes and the exact pitches going on. Or why they are happening harmonically. I can kind of see how the phrasing works and how you can interpret it as a dispute or interpret it as a conversation.

You can interpret it in many different ways as long as it makes sense to your mind. As I mentioned in the beginning of the episode we have this internal mandate to makes sense of what we hear.

And so as you begin to become a more Active Listener you will start making more connections between what is happening on the bandstand or in the album and you will connect it with show tunes.

Or you will connect it with Jazz solos. Or you will connect with what you just heard from another player.

And all of these things connect contribute to your enjoyment of this beautiful art form. So thank you very much for joining me for Episode 8) of Active Listening in Jazz and I will see you in Episode 9).

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Check out my Active Listening in Jazz for Non-Musicians Facebook Group. Join today to find out more.

See my Active Listening in Jazz for Non-Musicians Youtube Playlist.

Subscribe to the playlist to learn about new episodes.

Episode 1) Intro & Singlalong Dan Adler blog series

Episode 2) The Blues

Episode 3) Form

Episode 4) Miles Davis, ‘So What?’

Episode 5) Harmony & Improv

Episode 6) Jazz Expression

Episode 7) Rhythm Section

Episode 8) Story and Motif