This week’s Torah portion is Balak, which tells the story of a mythical non-Israelite prophet called Balaam (Bil’aam in Hebrew – בלעם).

The story of Balaam is one of the most baffling portions in the Torah.

First of all, it seems to have no significance to the plot of the Israelite travels in the desert. The story unfolds as a psycho-drama between Balak the king of Moab, and the (Midianite?) prophet-for-hire Balaam Ben Be’or, whom Balak is trying to convince to curse the Israelites. Finally when Balak succeeds, Balaam’s curse comes out as a blessing. In fact, this has become one of the most famous blessings in the Torah and the Liturgy:

מה טובו אהליך יעקב, משכנותיך ישראל

How goodly are your tents, Jacob, your dwellings, Israel

Secondly, the story is about a non-Israelite prophet who actually converses with God. Why would the Biblical editors choose to include such a story, which seems to imply that prophecy is universal?

Thirdly, there is the supernatural story of the talking Donkey that sees visions of angels blocking its way.

For all these reasons, it has been tempting for Biblical scholars to dismiss the story as pure fiction and treat it as a parable. In his book Who Wrote The Bible, Richard Friedman claims that the story of Balaam comes predominantly from the E or Elohist sources, i.e. it’s a folk tale that originated in the Northern tribes of Israel rather than Judah (with the possible exception of the Donkey story, which appears to be a later addition). This view is also supported by some of the imagery in Numbers 23, which features a multiplicity of Altars as was the custom in Northern Israel rather than in Jerusalem-centric Judah.

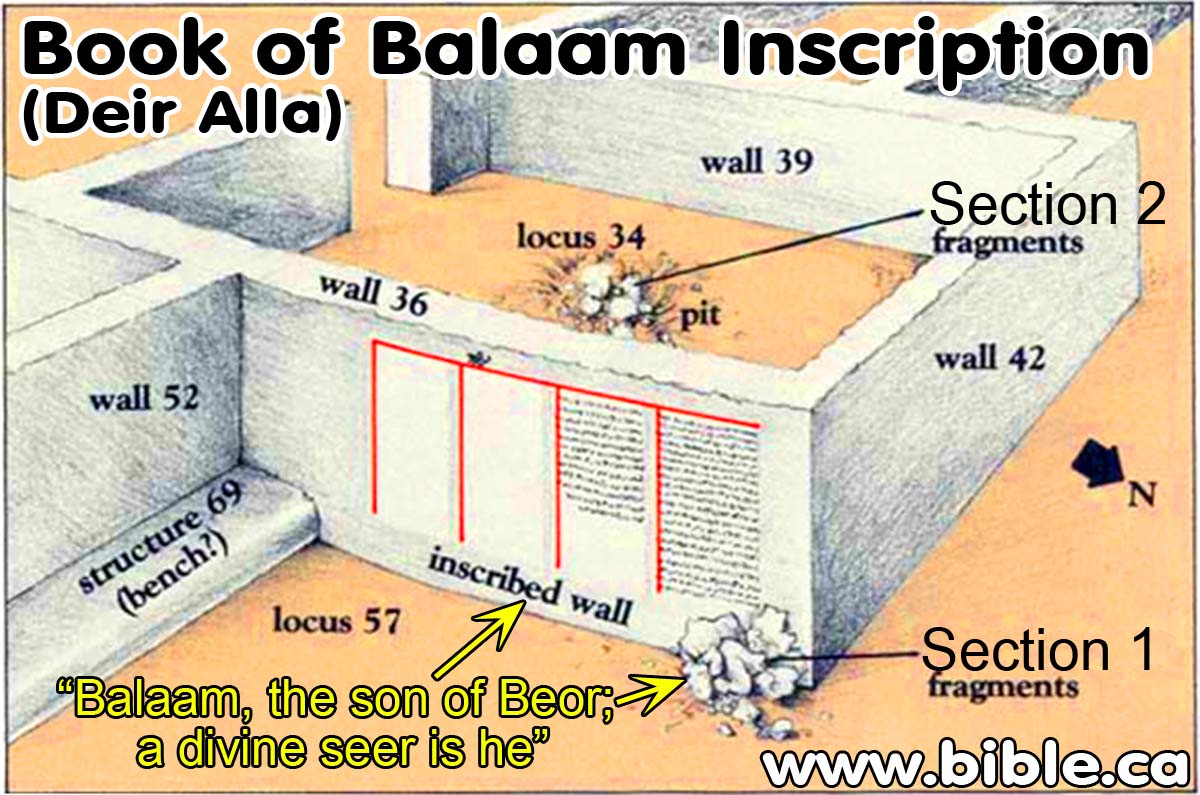

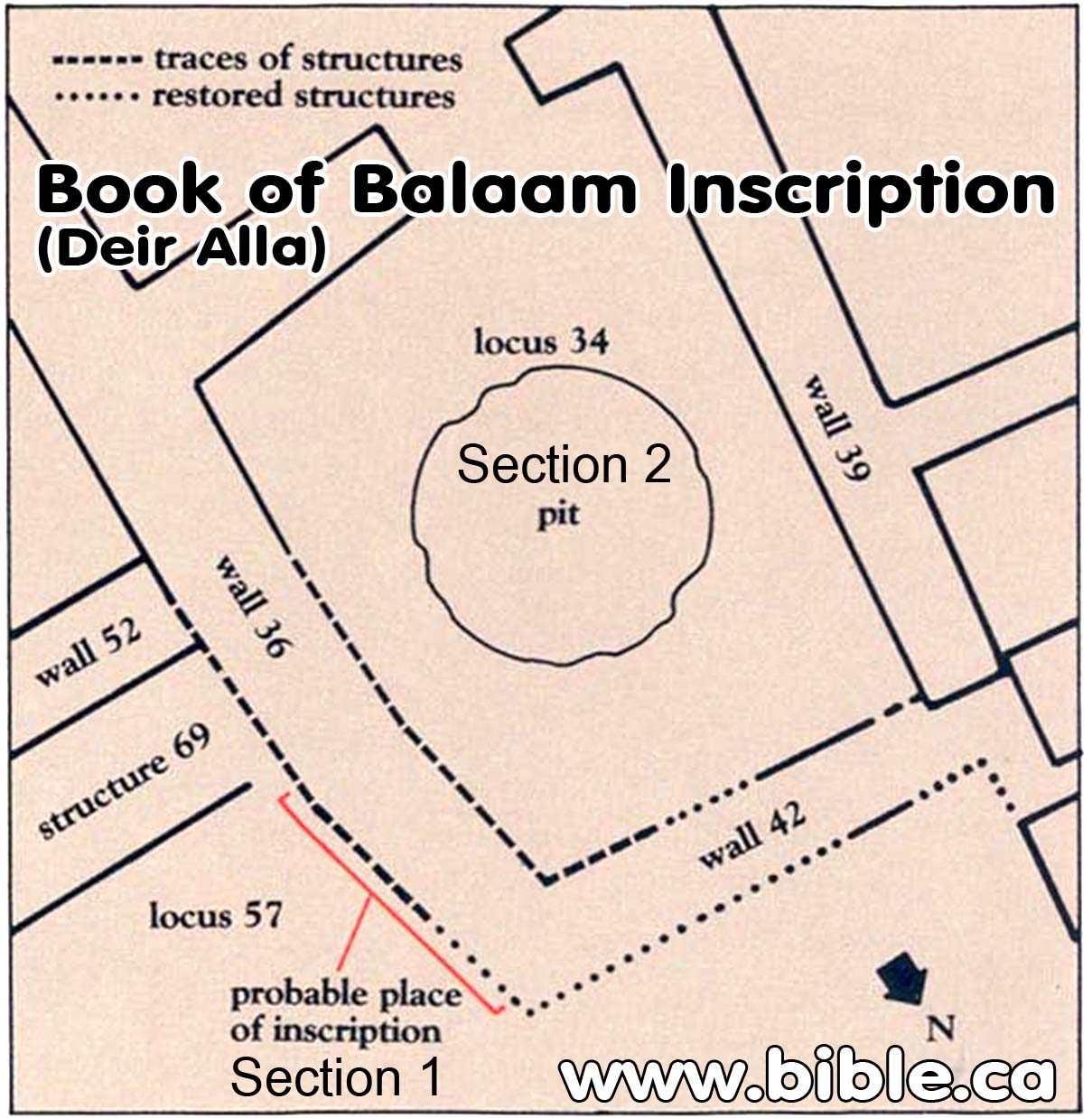

But this view of Balaam changed in 1967, when archeologists uncovered the Deir Alla inscription, which has been carbon-dated to around 840–760 BCE, and seems to imply that Balaam was indeed a real person. Some epigraphy experts date the writing style of the inscription to a later period around 700 BCE, which would place it after the destruction of Northern Israel, but carbon dating seems to support an earlier time frame. The location of Deir Alla may be linked to the biblical settlement of Succoth:

The inscription was part of a Temple (most likely Midianite) which was used to worship multiple Gods (Elohim):

The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies describes it as “the oldest example of a book in a West Semitic language written with the alphabet, and the oldest piece of Aramaic literature.” The inscription is written in ancient Hebrew letters, in a language that seems to be a local variation on Aramaic/Canaanite with some Hebrew syntax thrown in. It was painted in red and black inks on fragments of a plastered wall. The heading is in red, as are the passages that Balaam heard from God, and the rest of the inscription is in black ink.

There are 12 sections in the uncovered inscription and not all of them seem to be consecutive. According to Alexander Rofe, the fragments were discovered by a Dutch archeology team which worked in Jordan since 1960. The inscriptions were in bad shape and were painstakingly restored in Jerusalem and Holland over several years. Since 1972, the fragments are on display at the Archeological Museum in Amman Jordan:

The writing of ink on white plaster is suggestive of another Biblical text: Deuteronomy 27:4-5: “Therefore it shall be, when you have crossed over the Jordan, that on Mount Ebal you shall set up these stones, which I command you today, and you shall whitewash them with plater” (שיד or סיד).

Independent of the Deir Alla inscription, Israel Knohl, in his book Ha-Shem, dates Balaam’s main blessing poem (Numbers 24:4-9) to a much later period than the Sinai period. Based on verse 7: “his king shall be raised over Agag, and his kingship exalted”, he thinks this refers to King Saul’s victory over Agag the Amalekite (I Samuel 15:4-8).

Independent of the Deir Alla inscription, Israel Knohl, in his book Ha-Shem, dates Balaam’s main blessing poem (Numbers 24:4-9) to a much later period than the Sinai period. Based on verse 7: “his king shall be raised over Agag, and his kingship exalted”, he thinks this refers to King Saul’s victory over Agag the Amalekite (I Samuel 15:4-8).

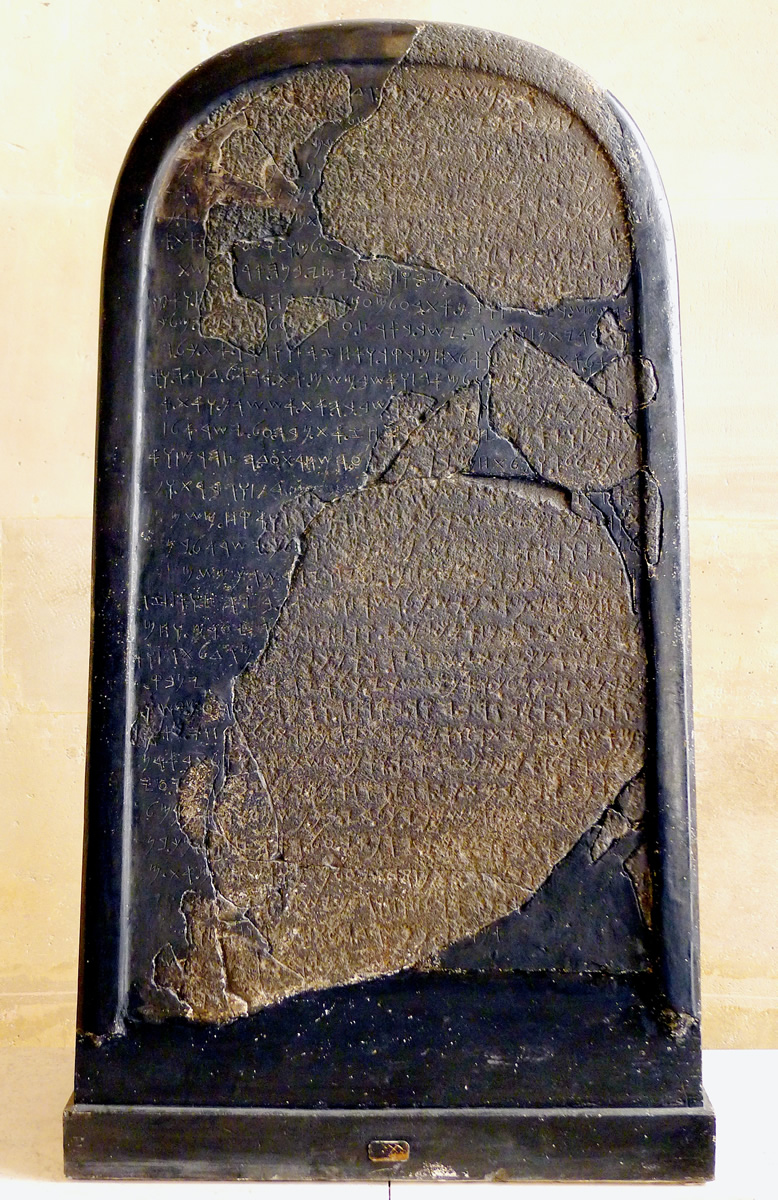

On the other hand, Knohl also cites Numbers 24:17 as possibly referring to the fear Israel instilled in Moab, which would more likely date the poem to the time of King Omri. This is much more consistent with the Deir Alla timing, as it dates to the 9th century BCE based on another famous inscription: The Mesha Stele.

The Mesha Stele (also known as the “Moabite Stone”) is a stele (inscribed stone) set up around 840 BCE by King Mesha of Moab (a kingdom located in modern Jordan). Mesha tells how Kemosh, the God of Moab, had been angry with his people and had allowed them to be subjugated to Israel, but at length Kemosh returned and assisted Mesha to throw off the yoke of Israel and restore the lands of Moab. Mesha describes his many building projects.

The Mesha Stele is the longest Iron Age inscription ever found in the region, constitutes the major evidence for the Moabite language, and is a “corner-stone of Semitic epigraphy and Israelite history”.The stele, whose story parallels, with some differences, an episode in the Bible’s Books of Kings (2 Kings 3:4–8), provides invaluable information on the Moabite language and the political relationship between Moab and Israel at one moment in the 9th century BCE. It is the most extensive inscription ever recovered that refers to the kingdom of Israel (the “House of Omri”); it bears the earliest certain extra-biblical reference to the Israelite God Adonai (יהוה), and the earliest mention of the “House of David” (i.e., the kingdom of Judah). It is also one of only four known ancient inscriptions interpreted to mention the term “Israel”, the others being the Merneptah Stele (1200 BCE), the Tel Dan Stele, and the Kurkh Monolith.

The Tel Dan Stele is a broken stele (inscribed stone) discovered in 1993–94 during excavations at Tel Dan in northern Israel. It consists of several fragments making up part of a triumphal inscription in Aramaic, left most probably by Hazael of Aram-Damascus, an important regional figure in the late 9th century BCE. I recently took a photo of the actual Tel Dan Stele while it was on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York:

Back to Balaam. Based on the recent archeological evidence, it seems that Balaam was a real-life well-known priest (Moabite or Midianite) who lived in the 9th century BCE. He was widely believed to be a genuine non-Israelite prophet. Even the Sages acknowledge this in Midrash Bamidbar Rabah 14:20 “There were three features possessed by the prophecy of Balaam that were absent from that of Moses: 1) Moses did not know who was speaking with him, whereas Balaam knew who was speaking with him; 2) Moses did not know when the Holy One Blessed Be He would speak with him, whereas Balaam knew…3) Balaam spoke with Him whenever he pleased…Moses, however, did not speak with Him whenever he wished.”

Based on the Balaam inscription, his prophesies were mostly morbid apocalyptic imagery, like this excerpt: “..sew the skies shut with your thick cloud! There let there be darkness and no (7) perpetual shining and n[o] radiance! For you will put a sea[l upon the thick] cloud of darkness and you will not remove it forever! For the swift has (8) reproached the eagle, the voice of vultures resounds”.

In summary, all the evidence seems to support the theory that the real historical Balaam was a well known religious figure in the ancient Near East around the 8-9 century BCE. He had a wide reputation for delivering morbid prophesies and curses and was a high priest in his own temple. Assuming that the Biblical editors knew all this, and knew that their readers knew it as well, it becomes more obvious why they felt inclined to include the story of Balaam’s blessings to Israel in so much detail in the Balak portion. The story is also mentioned in Numbers 31:8,16 (where Balaam is killed in battle), Deutoronomy 23:5-6, in the book of Micah 6:5 (the Haftara for Balak), as well as in Joshua 13:22 and Nehemiah 13:2.