Halfway between Dayenu and the Meal lies the key phrase of the entire Seder:

When we read this in 21st century America, it sounds like a distant metaphor. You can find any number of Rabbinical sermons about “finding your own Egypt”, i.e. freeing yourself of some form of self-inflicted slavery to gadgets, money, peer approval, etc.

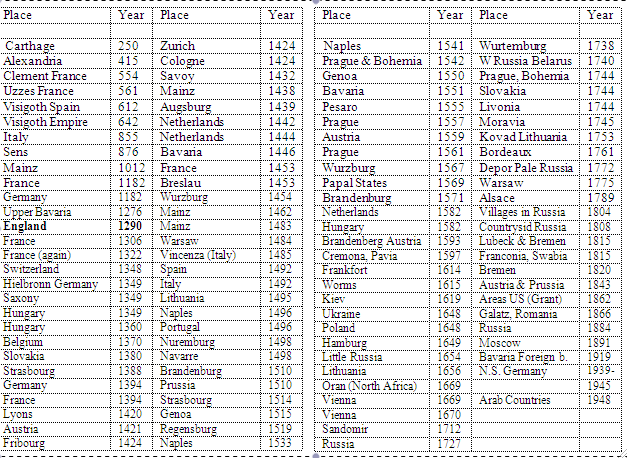

However, as we peek back into Jewish history, we find that a physical Exodus or Expulsion from one place to another really did occur in almost every generation. Even in generations where Jews were allowed to stay put, they were subjected to various degrees of oppression: sometimes physical, usually financial, and always humiliating.

I discussed documented accounts of anti-Semitism in Persia and Egypt in my post about Purim, and of course we all know the Hannukkah Story.

What I want to remind you here is that Jewish Freedom was an oxymoron in almost all countries at almost all times in History. At best, Jews were tolerated, never equal to other citizens, and never truly free.

Roman and Byzantine Empires

After the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD, and the bloodbaths that followed the Bar Kokhba Revolt which ended on the 9th of Av 135 AD, Jews in the land of Israel temporarily enjoyed a limited form of religious toleration: they were considered a Religio Licita: a Licensed Religion.

This started rapidly deteriorating as Christianity was adopted by the Roman empire. In the year 300, the Council of Elvira decreed several limitation on how Christians should interact with Jews: they could not marry Jews, they cannot accept Jewish blessings over their crops, and they could not eat a meal with a Jew (from which we can deduce that Jews were willing to eat meals at Roman homes despite the laws of Kashrut).

The Council of Nicea in 325 AD separated the dates of the Christian Sabbath from the Jewish Shabbat, and separated Easter from Passover: “Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd”.

The Mulsim Invasion

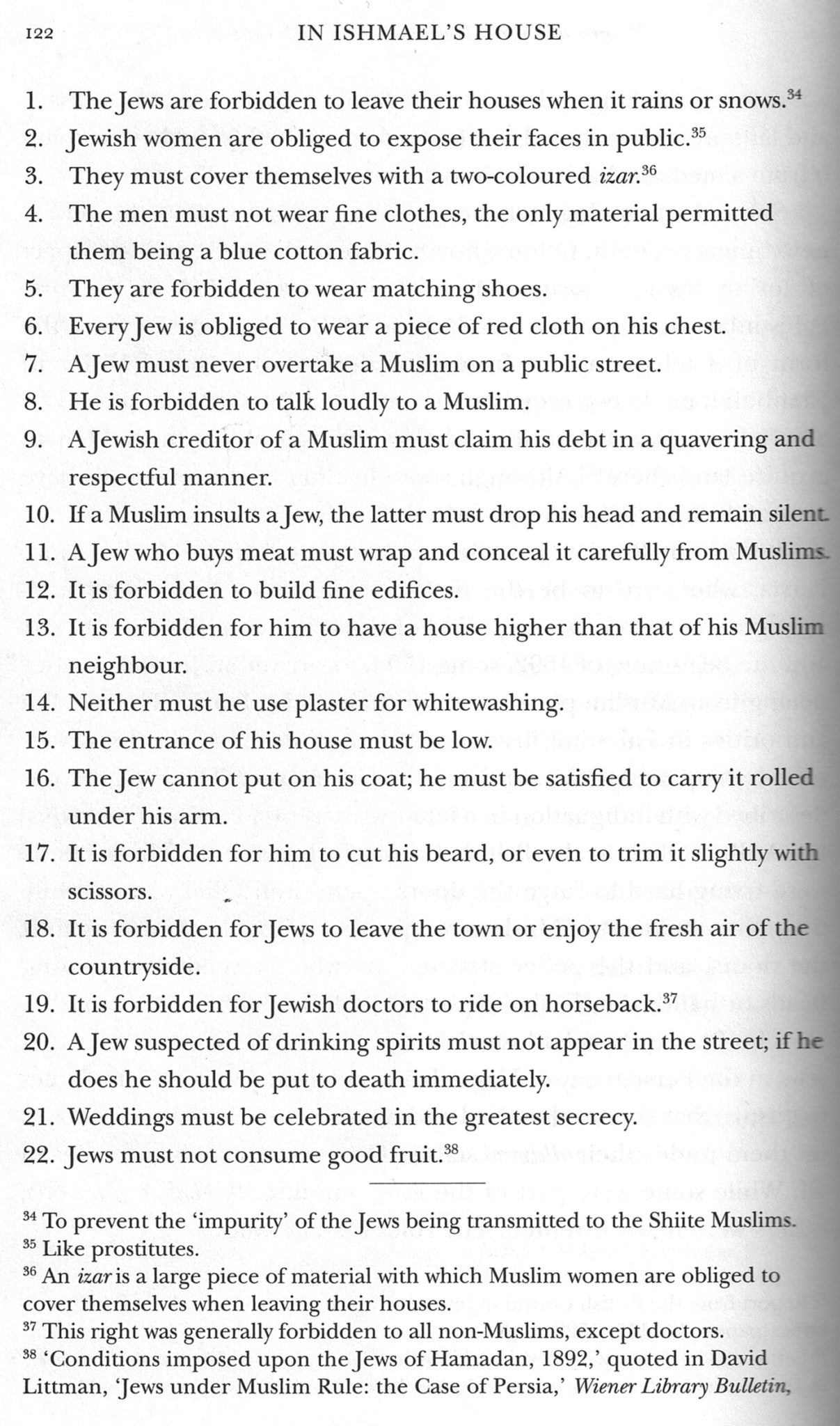

Following the Islamic occupation of the land of Israel, Arabia, Babylon, Persia, North Africa and Spain, the Jews had to learn to accept their new status as a dhimmi and pay a special tax called a Jizya. The laws of dhimmitude were interpreted differently in different Muslim lands at different periods, but they always contained an element of humiliation, denigrating the Jew to remind him of his inferior status to his Muslim benefactor. In his book In Ishmael’s House, Martin Gilbert shows the following 22 rules which were imposed on Jews in the Persian city of Hamadan:

The Middle Ages

The Crusades brought about death and devastation not just upon the Jews of the land of Israel, but also on the Jews of Germany (Ashkenaz). In 1084, Jews fleeing from pogroms in Mainz (Magenza) and Worms (Vormiza) ignited by the crusades took refuge with their relatives in Speyer (Shpaira). They came at the instigation of bishop Rüdiger Huzmann, who invited a larger number of Jews to live in his town with the expressed approval of emperor Henry IV. But in 1096, a series of pogroms hit the Jews of Germany known as the Rheinland Massacres, in which thousands of Jews were murdered and the Jewish quarters of their towns destroyed. One remnant of these massacres is the U’Netaneh Tokef prayer, which is said to have been composed by Rabbi Amnon of Mainz as he was being tortured to death.

Jewish Expulsions

The following map shows the main Jewish Expulsions during the Middle Ages:

Here is a partial timeline of Jewish Expulsions:

A more complete list of Expulsions and Pogroms can be found: here

The Spanish Inquisition and Expulsion

While many people associate the Inquisition with Spain and Portugal, it was actually instituted by Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) in Rome. By 1255, the Inquisition was in full gear throughout Central and Western Europe; although it was never instituted in England or Scandinavia.

In the beginning, the Inquisition dealt only with Christian heretics and did not interfere with the affairs of Jews. However, in 1242, the Inquisition condemned the Talmud and burned thousands of volumes. In 1288, the first mass burning of Jews on the stake took place in France.

In Spain, an anti-Jewish riot broke out in Seville on March 15, 1391, after years of incitement. Several Jews were slain; but the nobles, who protected them, quickly repressed the uprising. Anti-Semitic unrest and lawlessness persisted until a full-scale pogrom broke out on June 6, 1391. The infuriated populace attacked the ghetto from all sides, plundering and burning the houses. Many fell victims to the mob’s fury, although most of the Jews accepted baptism to save their lives. The violence spread from town to town, with thousands more Jews murdered or forcibly converted in Cordoba, Toledo, Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Majorca, and many other centers within less than a year. This was a turning point in the history of Spanish Jews, as the great majority escaped death by converting to Christianity and set in motion the Converso phenomenon. They were labeled “Marranos”, which means swine, because the Church did not consider them true Christians. The converters were also called Crypto-Jews because some worshiped Judaism in secret.

In 1481 the Inquisition started in Spain and ultimately surpassed the medieval Inquisition, in both scope and intensity. Conversos (Secret Jews) and New Christians (Converts who were falsely accused of being Secret Jews) were targeted because of their close relations to the Jewish community, many of whom were Jews in all but their name. Fear of Jewish influence led Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand to write a petition to the Pope asking permission to start an Inquisition in Spain. In 1483 Tomas de Torquemada became the inquisitor-general for most of Spain, he set tribunals in many cities. More than 13,000 Conversos were put on trial during the first 12 years of the Spanish Inquisition. Hoping to eliminate ties between the Jewish community and Conversos, the Jews of Spain were expelled in 1492. Watch this video where former Israeli president Yitzhak Navon browses through a Spanish archive for the The Alhambra Decree of Expulsion and Christopher Columbus’ Royal Sanction to sail:

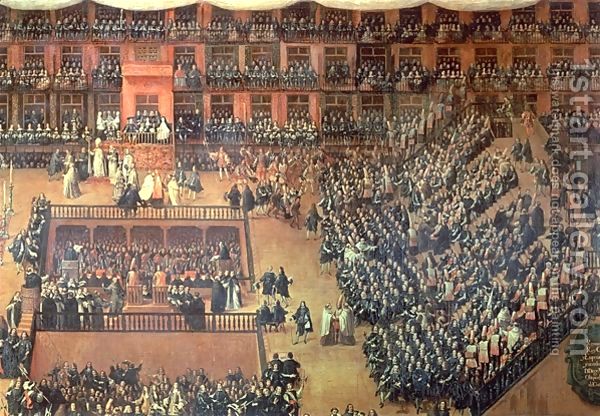

The following is a metal bench commemorating the Auto de Fe in the Plaza Mayor, Madrid, 30 June 1680. This Inquisition scene was made famous by a painting in the Prado by Francisco Rizi shown below:

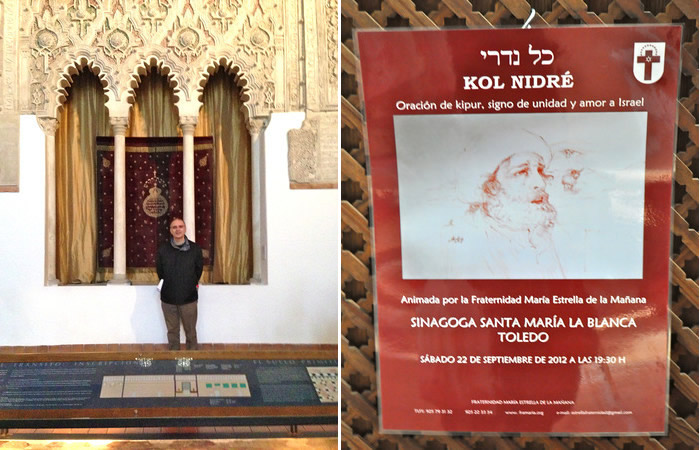

The following pictures are from my trip to Toledo where two Jewish synagogues remain open to tourists, but have no local Jews to worship in them. The picture on the left is inside the El-Transito Synagogue, which was converted to a church after the expulsion, and now restored into a Jewish Museum. The picture on the right is a poster from Santa Maria La Blanca (literally Saint Mary the White, originally known as the Ibn Shushan Synagogue). It was Erected in 1180, and is considered the oldest synagogue building in Europe still standing. It was converted to a church in the 15th century, after the expulsion in 1492. In the photo, the Christian nuns that run the site are inviting the population of Toledo to celebrate Kol Nidrei 2012. Underneath, it says they will perform the song of Kipur as a sign of unity and love of Israel. Notice the logo at the top right: a cross with a Magen David in the middle.

By the second half of the 18th century, the Inquisition abated, due to the spread of enlightened ideas and lack of resources. The last auto de fe in Portugal took place on October 27, 1765. Not until 1808, during the brief reign of Joseph Bonaparte, was the Inquisition abolished in Spain. An estimated 31,912 heretics were burned at the stake, 17,659 were burned in effigy and 291,450 made reconciliations in the Spanish Inquisition. In Portugal, about 40,000 cases were tried, although only 1,800 were burned, the rest made penance.

The Inquisition was not limited to Europe; it also spread to Spanish and Portugese colonies in the New World and Asia. Many Jews and Conversos fled from Portugal and Spain to the New World seeking greater security and economic opportunities. Branches of the Portugese Inquisition were set up in Goa and Brazil. Spanish tribunals and auto de fes were set up in Mexico, the Philippine Islands, Guatemala, Peru, New Granada and the Canary Islands. By the late 18th century, most of these were dissolved.

The inquisition remained the nightmare of the Jews for more than 400 years! It is not a relic of ancient history: it only subsided some 200 years ago, and its effects are felt until today. Watch this video where former Israeli president Yitzhak Navon meets the last Marranos still living in Portugal today:

The 16th Century: The Jewish Ghetto and Yellow Badge

The 16th century ushered in a new era for the Jews of Europe: forced separation and demarcation. The first Ghetto was created in Venice (in the Venetian language it was named “ghèto”). The Venetian Ghetto was instituted in 1516, although political restrictions on Jewish rights and residences had existed before that date.

Ghettos popped up all over Europe. Another well-known example is that of Prague: From 1522-1541, the population of the ghetto almost doubled due to influx of Jews expelled from Moravia, Germany, Austria and Spain. Inside the ghetto the Jewish people had their own town hall with a prized small bell used to call attendees to meetings. The Jews even had permission to fly their own flag. Jewish living in the ghetto prospered in many diverse professions such as mathematicians, astronomers, geographers, historians, philosophers, and artists. Note the yellow cap in the center of the Star of David. This was the mark which the Jews of Prague had to wear at all times:

As you can see the concept of a Yellow Badge did not originate with the Nazis. In the early Islamic period, non-Muslims were required to wear distinctive marks in public, such as metal seals fixed around their necks and wear special emblems on their clothes. The yellow badge was first introduced by a caliph in Baghdad in the 9th century, and spread to the West in medieval times. Even in public baths, non-Muslims wore medallions suspended from cords around their necks so no one would mistake them for Muslims. Belts, headgear, shoes, armbands and/or cloth patches were also used. Under Sunni rules, they were not allowed to use the same baths.In 1005 the Jews of Egypt were ordered to wear bells on their garments.

In Medieval Europe, Jews were also required to wear identifying badges. In 1227, the Synod of Narbonnee, in canon 3, ruled: “That Jews may be distinguished from others, we decree and emphatically command that in the center of the breast (of their garments) they shall wear an oval b

In Medieval Europe, Jews were also required to wear identifying badges. In 1227, the Synod of Narbonnee, in canon 3, ruled: “That Jews may be distinguished from others, we decree and emphatically command that in the center of the breast (of their garments) they shall wear an oval b

adge, the measure of one finger in width and one half a palm in height”.

In 1228, James I of Aragon ordered Jews of Aragon to wear the badge. In 1274, Edward I of England enacted the Statute of Jewry, which also included a requirement: “Each Jew, after he is seven years old, shall wear a distinguishing mark on his outer garment, that is to say, in the form of two Tables joined, of yellow felt of the length of six inches and of the breadth of three inches.”

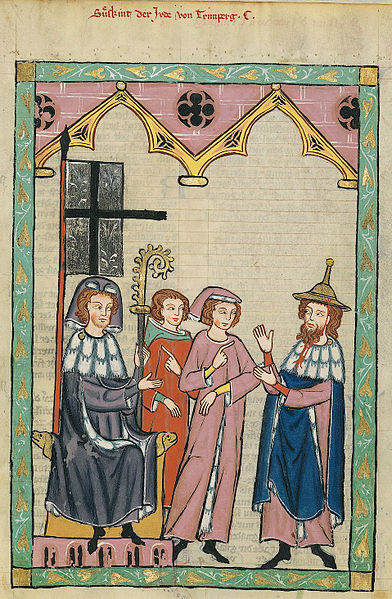

In German-speaking Europe, a requirement for a badge was less common than the Judenhut or Pileum cornutum (a cone-shaped head dress, common in medieval illustrations of Jews):

The Jews of Hungary

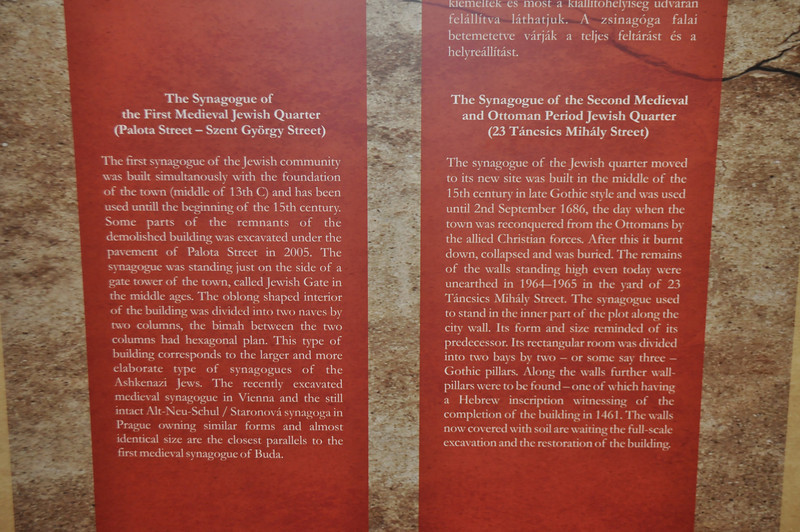

In Hungary, Jews lived in Buda (part of Budapest) as merchants, shopkeepers and craftsmen. A Jewish community formed in the late 11th-early 12th century. A synagogue was built in 1307, but was destroyed a number of years later. The Jews were expelled in 1348 and again in 1360, but were allowed to return shortly afterward. A second synagogue was built in Buda in 1461 and survived for many years. The situation for Jews took a turn for the worse in the 1490’s, their property was confiscated and loans to Jews were not paid. For the fifteen years before the Ottoman conquest of Buda, a period of unrest ensued.

Jews in 17th-20th Century Europe

As liberalism and enlightenment swept Europe, you might think that the Jews would have benefitted from that, and to a certain degree they did, but it was always in a very limited form and it often involved taking one step forward and two steps back.

In 1581, the northern provinces of Holland declared independence from Spanish rule and ushered in a period of tolerance. Spanish New Christians, Jews who were forced to convert to Christianity but k

ept their Jewish identity in hiding, were allowed to settle there and recreate a Jewish community which had informal emancipation until 1796, when Dutch Jews were formally emancipated.

In some countries, Jewish Emancipation came with a single act. In others, limited rights were granted first in the hope of “changing” the Jews “for the better.”

Years when legal equality was granted to Jews

Year Country

1264 Poland

1789 United States

1791 France

1796 Batavian (Dutch) Republic

1812 Prussia

1830 Belgium, Greece

1832 Canada

1835 Sweden-Norway

1839 Ottoman Empire

1849 Denmark

1856 Switzerland

1858 United Kingdom

1861 Italy

1867 Austria-Hungary

1871 Germany

1878 Bulgaria, Serbia

1890 Brazil

1910 Spain, Portugal

1917 Russia

1923 Romania

France is often praised as the first European nation to grant Jews emancipation in continental Europe in the 18th century. Conte de Clermont‑Tonnere, in his famous speech to the National Assembly (December 1789), explicitly demanded that the Jews not be excluded from article X of the Declaration of Rights (“No man ought to be molested because of his opinions, including his religious opinions”). Therefore, he said, “The Jews should be denied everything as a nation, but granted everything as individuals.”

This was codified in a decree of the French National Assembly in 1791. However, just a few years later, in 1806, Napoleon called for an assembly of Jewish notables and gave them a list of 12 questions to determine their loyalty. The list of questions and answers is here. Two years later, in 1808, Napoleon issued his Infamous Decree which cancelled all debts owed by Christians to Jews. It also banned Jews from any “business, negotiation, or any type of commerce” except by a special license, and outlawed any transaction with “unlicensed Jews”.

Jewish Hopes for Emancipation in Germany

The story of Jewish emancipation in Germany was more complicated and we all know how it ended with the Nuremberg Laws and the Holocaust. Prussia gave a limited form of emancipation to its Jews in 1815, but it had a strong caveat: no foreign Jews would be allowed to settle or marry native Jews. In 1818, Jews were excluded from all academic positions (causing Heinrich Heine , Eduard Gans , and others to convert to Christianity); the following January Jewish officials in Westphalia and the Rhineland were dismissed (including Heinrich Marx, father of Karl Marx ). The benefits of the 1812 edict had not been applied to Posen (where the laws of 1750 and 1797 remained in force), while its restrictions were applied to the western territories. Thus the Napoleonic “infamous decree,” which by then had lapsed in France, was renewed by Prussia in 1818 to cover the Rhineland for an indefinite period. Prussian Jewry’s legal position was encumbered by the coexistence of 22 different legislative systems with the various provinces. The king actively encouraged conversion to Christianity and prohibited conversion to Judaism.

The German federal edicts of 1815 merely held out the prospect of full equality; but it was not genuinely implemented at that time, and even the promises which had been made were modified. In Austria many laws restricting the trade and traffic of Jewish subjects remained in force until the middle of the 19th century in spite of the patent of toleration. Some of the crown lands, such as Styria and Upper Austria, forbade any Jews to settle within their territory; in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia many cities were closed to them. The Jews were also burdened with heavy taxes and imposts.

The Jewish Reformation or Haskalah originated in Galicia (Germany, Poland and Central Europe) and later spread to Eastern Europe (Lithuania and other provinces of the Pale of Jewish Settlement1). The Haskalah was characterized by a scientific approach to religion in which secular culture and philosophy became a central value.

Moses Mendelssohn (1726-1789) is considered the father of the Haskalah. Mendelssohn was a philosopher  with ideas from the general Enlightenment. Frederick the Great declared him a “Jew under extraordinary protection” and he won a prize from the Prussian Academy of Sciences on his “treatise on evidence in the metaphysical sciences.” He wrote in German, the language of the scholars. He represented Judaism as a non-dogmatic, rational faith that is open to modernity and change. He called for secular education and a revival of Hebrew language and literature. He initiated a translation of the Torah into German with Hebrew letters, tried to improve the legal situation of the Jews and the relationship between Jews and Christians, and argued for Jewish tolerance and humanity.

with ideas from the general Enlightenment. Frederick the Great declared him a “Jew under extraordinary protection” and he won a prize from the Prussian Academy of Sciences on his “treatise on evidence in the metaphysical sciences.” He wrote in German, the language of the scholars. He represented Judaism as a non-dogmatic, rational faith that is open to modernity and change. He called for secular education and a revival of Hebrew language and literature. He initiated a translation of the Torah into German with Hebrew letters, tried to improve the legal situation of the Jews and the relationship between Jews and Christians, and argued for Jewish tolerance and humanity.

Even  before Nazism, many anti-semitic texts originated in Germany. For example, Wilhelm Marr’s The Victory of Judaism Over Germandom, published in 1879. Marr describes his writing as “a ‘scream of pain’ coming from the oppressed”. He sees Germans as having already lost the battle with Jewry: “Judaism has triumphed on a worldwide historical, basis. I shall bring the news of a lost battle and of the victory of the enemy and all of that I shall do without offering excuses for the defeated army.”

before Nazism, many anti-semitic texts originated in Germany. For example, Wilhelm Marr’s The Victory of Judaism Over Germandom, published in 1879. Marr describes his writing as “a ‘scream of pain’ coming from the oppressed”. He sees Germans as having already lost the battle with Jewry: “Judaism has triumphed on a worldwide historical, basis. I shall bring the news of a lost battle and of the victory of the enemy and all of that I shall do without offering excuses for the defeated army.”

Jews In Russia

The history of Jews in Russia is intimately tied to the Pale Of Settlement: a region of Imperial Russia in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed and beyond which Jewish permanent residency was generally prohibited. Officially banned in 1479, no Jews lived in the Russian Empire until Tsarina Catherine II conquered a major portion of Polish territory in 1791, instantly inheriting the largest single concentration of Jews in the world.

The Pale comprised about 20% of the territory of European Russia, and largely corresponded to historical borders of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Jews were also excluded from residency at a number of cities within the Pale. A limited number of categories of Jews were allowed to live outside the pale.

From 1791 to 1917, there were differing reconfigurations of the boundaries of the Pale, such that certain areas were variously open or shut to Jewish residency, such as the Caucasus. At times, Jews were forbi dden to live in agricultural communities, or certain cities, as in Kiev, Sevastopol and Yalta, and forced to move to small provincial towns, thus fostering the rise of the shtetls. In some periods, special dispensations were given for Jews to live in the major imperial cities, but these were tenuous, and several thousand Jews were expelled to the Pale from Saint Petersburg and Moscow as late as 1891.

dden to live in agricultural communities, or certain cities, as in Kiev, Sevastopol and Yalta, and forced to move to small provincial towns, thus fostering the rise of the shtetls. In some periods, special dispensations were given for Jews to live in the major imperial cities, but these were tenuous, and several thousand Jews were expelled to the Pale from Saint Petersburg and Moscow as late as 1891.

During World War I, the Pale lost its rigid hold on the Jewish population when large numbers of Jews fled into the Russian interior to escape the invading German army. On March 20 (April 2), 1917, the Pale was abolished by the Provisional Government decree, On abolition of confessional and national restrictions. A large portion of the Pale, together with its Jewish population, became part of Poland.

Here is a short video about the history of the Pale of Settlement:

The Failure of Emancipation

T he failure of Jews to obtain full equality in any of the lands in which they lived (except America) was one of the driving forces behind the emergence of political Zionism. No matter how much they assimilated, secularized, reformed, and watered down their exterior expressions of Judaism, their acceptance as equals in

he failure of Jews to obtain full equality in any of the lands in which they lived (except America) was one of the driving forces behind the emergence of political Zionism. No matter how much they assimilated, secularized, reformed, and watered down their exterior expressions of Judaism, their acceptance as equals in

European and Muslim societies was limited, and subject to the whim of political leaders.

Coincidentally, the 19th century (Spring of Nations) and early 20th century (World War I) saw the rise of nationalism and the emergence of the modern concept of a nation-state. Four massive empires crumbled in the aftermath of World War I and were divided up into nation-states: The German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman Empires.

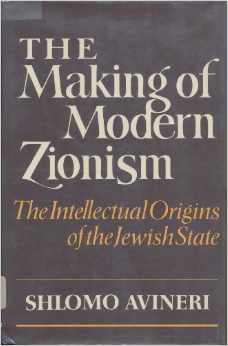

As Shlomo Avineri argues in the book above, the rise of European nationalism brought with it new national narratives which excluded the Jew, not on a religious basis, but on the basis of not being part of the shared formative narrative of the nation (e.g. Germanic tribes, Franks, Gauls, etc.).

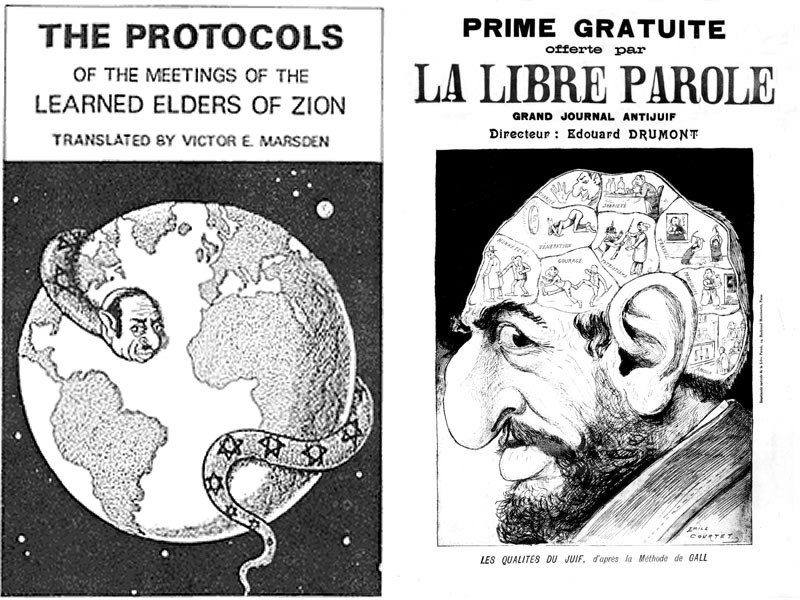

On top of that, Wilhelm Marr in Germany and Edouard Drumond in France, and the proliferation of the forged document known as the Protocols Of The Elders of Zion, brought about a new form of Racial antisemitism, against which the Jews had no recourse. If Jewish “evil” lies in their genes, in their blood, and in their crooked nose rather than in their religion or social behavior, then there was nothing they could ever hope to do about it.

Conversion to Christianity or Islam was no longer enough. A Jew would remain a Jew even if he or she changed their religion. Under these circumstances, Theodor Herzl reached the conclusion that there could be no hope for the Jew to assimilate into European society, and that the only solution to the Jewish Question would be to reconstitute the Jewish national home in the land of Israel.

So, when you read the Haggadah on Passover and reach these words: “In each and every generation a person must see himself as if he personally had an exodus from Egypt” – take a moment to reflect on Jewish history: the forced expulsions, the seizing of possessions, the denial of property ownership, the denial of education and livelihood, the pogroms and massacres, the burning of books, and the humiliation and vilification which made up every generation of our history. We are truly lucky to be living as equals in America, and to have realized the vision of rebuilding our national home in the land of Israel.