In previous posts I proposed some non-mystical ways of thinking about the Jewish God which may appeal to people who view themselves as atheists or agnostics. My goal is not to try and persuade people who do believe in God to change their conception. Quite the opposite. My goal is to show Jews who do not believe in God that Judaism has something rich and rewarding to offer them as well.

No single issue cuts to the heart of the matter of belief as does the question of prayer. Even if you are willing to accept an abstract, non-creationist, non-intervening God, there still remains the question: why would you pray to him/her/it? If you believe God does not really exist as a conscious entity floating around the outside of the universe, judging people and directing the forces of nature, then what reason would you possibly have to ask him to answer your prayers?

I hope to show you in this article that Jewish Prayer has nothing to do with asking God for specific requests and expecting him to answer our prayers. That is a pagan idea that was uprooted from Judaism in ancient times. I already showed you in a previous article that our Talmudic sages had zero tolerance for Jews who called on God to intervene in daily life and expected him to actually do so – they were excommunicated from Jewish society.

Jewish Prayer can be viewed as a practical psychological tool for everyday life. Whether you use it daily or weekly or just occasionally, it is uniquely designed to complement our hectic lifestyle by adding a self-administered spiritual dimension that we all need, but often don’t realize that we are lacking.

Many secular Jews are introduced to prayer when they lose a parent,and someone urges them to say The Mourner’s Kaddish, the “Blues” of Judaism. If you spend some time researching the Kaddish, its origins and its meaning, you will find that it celebrates life rather than mourning the person who passed away. Countless books have been written about the Kaddish prayer and its therapeutic effect on the soul of the mourner, which makes it a perfect place to start comprehending the spiritual significance of Jewish prayer.

Let’s start by analyzing Jewish Prayer through the lens of the modern discipline of Positive Psychology.

In his book Flourish, Martin Seligman defines Authentic Happiness as PERMA: Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.

Of these five, Seligman tends to concentrate on three in his video lectures: Positive Emotions (external happiness), Engagement, and Meaning.

Engagement and Meaning are huge topics unto themselves, so I will get back to them in another post.

One of the key methods by which Seligman suggests people should increase Positive Emotion in their life is by appreciation and thankfulness. In Chapter 2 of his book: “Creating Your Happiness: Positive Psychology Exercises That Work”, he describes the “Gratitude Visit” – where you identify someone who has had a positive influence on you in the past and pay them a surprise visit to express your gratitude. He describes a “what-went-well” journal, where you record positive daily occurrences in your life, etc.

Another major proponent of Positive Psychology is secular Israeli Professor Tal Ben Shachar. Ben-Shachar’s motto is: “When you appreciate the Good, the Good appreciates” (analogous to stocks appreciating in value). In his book “Being Happy”, Ben-Shachar also talks about acceptance as a key ingredient in happiness: accepting failure and success, accepting emotions and imperfections.

Another major proponent of Positive Psychology is secular Israeli Professor Tal Ben Shachar. Ben-Shachar’s motto is: “When you appreciate the Good, the Good appreciates” (analogous to stocks appreciating in value). In his book “Being Happy”, Ben-Shachar also talks about acceptance as a key ingredient in happiness: accepting failure and success, accepting emotions and imperfections.

Are you beginning to see the connection to Jewish Prayer? At least one third of Jewish Prayer is about gratitude and acceptance.

Jewish Prayers vary greatly from one religious group to another and even by community. If you compare two Siddurs, you are likely to find major differences.  What this means is that you can pick and choose those prayers that are meaningful to you, or those which are customary in your congregation.

What this means is that you can pick and choose those prayers that are meaningful to you, or those which are customary in your congregation.

Let’s start with some examples from the morning sequence as explained by Rabbi Israel Meir Lau in his book Practical Judaism. Some of these prayers are designed to be said in private, and some are communal.

The very first words of Jewish Prayer in the morning are an appreciation of waking up and returning to consciousness. Since modern science cannot tell us what happens to our consciousness when we sleep, we imagine that we have “deposited” our soul with God for the night, and we thank him for returning it to us in the morning. The exact imagery is not as important as the fact that we start the day by acknowledging that it is a miracle that we wake up each morning conscious, rejuvenated, and ready to face a new day:

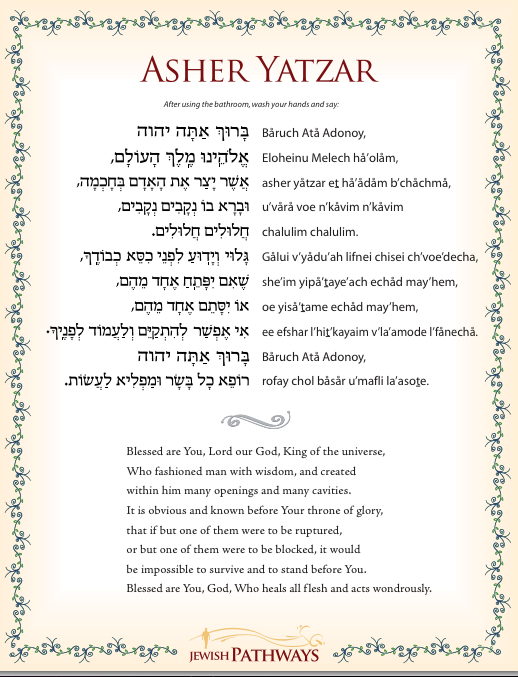

After washing the hands and going to the bathroom, Judaism offers the Asher Yatzar blessing that you may find comical at first reading. But, as you think about it a bit more in the context of Positive Psychology, you may come to appreciate how perfectly it describes all the things that can go wrong with our bodies, and how thankful we should be when everything works as advertised:

After washing the hands and going to the bathroom, Judaism offers the Asher Yatzar blessing that you may find comical at first reading. But, as you think about it a bit more in the context of Positive Psychology, you may come to appreciate how perfectly it describes all the things that can go wrong with our bodies, and how thankful we should be when everything works as advertised:

Gratitude and acceptance of imperfections go hand in hand in Jewish Prayer, by naming God as an abstract model of unattainable perfection, and by asking for the wisdom to make good choices. Judaism recognizes that our life is a struggle between the evil inclination (Yetzer Hara) and the good inclination (Yetzer Hatov) – and we remind ourselves daily to distance ourselves from wrongdoing.

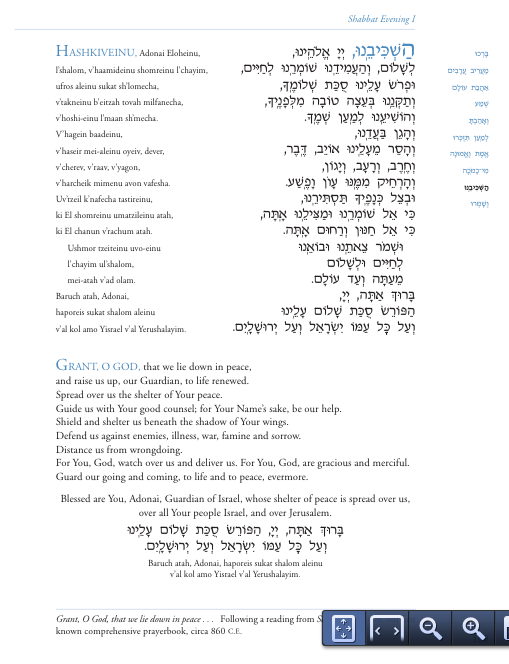

Prayers also recognize that there are circumstances which are beyond our control, and that sometimes all we can do is hope and pray that we will avoid them. The last prayer of the day, which is also used at Shabbat services, Hashkivenu, is a wonderful example of all of these ideas combined.

Behavioral Economics and Psychology

The need to remind ourselves often of our moral obligations is another theme that is prevalent throughout Jewish Prayer. It is also a central theme in the study of Behavioral Economics and Psychology, especially in the work of another secular Israeli-born professor: Dan Ariely.

In his book The Honest Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone–Especially Ourselves Ariely demonstrates through carefully crafted empirical experiments that most people will cheat when given the opportunity, but not by too much. He recast the Jewish theory of evil versus good inclinations into more secular terms: we cheat by as much as we can get away with and still be able to look ourselves in the mirror. He calls it our “fudge factor”

In his book The Honest Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone–Especially Ourselves Ariely demonstrates through carefully crafted empirical experiments that most people will cheat when given the opportunity, but not by too much. He recast the Jewish theory of evil versus good inclinations into more secular terms: we cheat by as much as we can get away with and still be able to look ourselves in the mirror. He calls it our “fudge factor”

How do we improve our “fudge factor” or make our moral code less buggy? Ariely found that asking people to recall the Ten Commandments brings their cheating down to zero! Later, he generalized this, and found that any regular reminder or a moral code or code of ethics has the same effect.

My point with this example is that Judaism figured this out a long time ago. Of course, this doesn’t mean that every person who prays will become a saint. Unfortunately, there are many religious Jews who pray every day and still commit crimes. However, constantly reminding ourselves to “do the right thing” and “not do the wrong thing” is one of the only tools we have at our disposal for moral self-improvement.

Yom Kippur is entirely about this one idea. It is not necessarily about God judging us, but about us taking a whole day to judge ourselves honestly. Weighing our deeds as we stand in front of the mirror, and vowing to correct those deeds that push us over the edge of our morality.

The Ahsamnu-Bagadnu prayer is sometimes called Vidui (confession). But its goal is not to list some sins and then receive an instant blank slate from God. It serves to remind us, through an alphabetical list of bad deeds, all the ways in which we may have betrayed our own moral code, and as we saw from Ariely’s examples, contemplating our moral code in an honest way, is half the battle towards improving our behavior. There is a beautiful reform version of this prayer in English that includes the following two lines:

…

For condemning in our children the faults we tolerate in ourselves,

and for condemning in our parents the faults we tolerate in ourselves.

…

The beauty of these two lines is that the phrasing helps us expose a double standard in our morality, and may give us pause the next time we are about to yell at our parents or children.

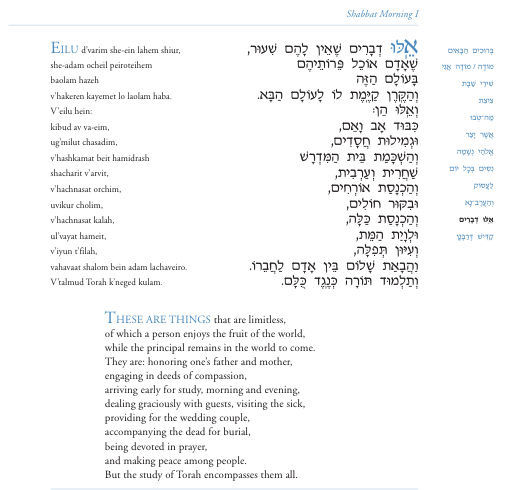

And on the flip side, the daily and weekly Eilu Dvarim prayer reminds us of good deeds which we should aim to perform:

The God of Prayers

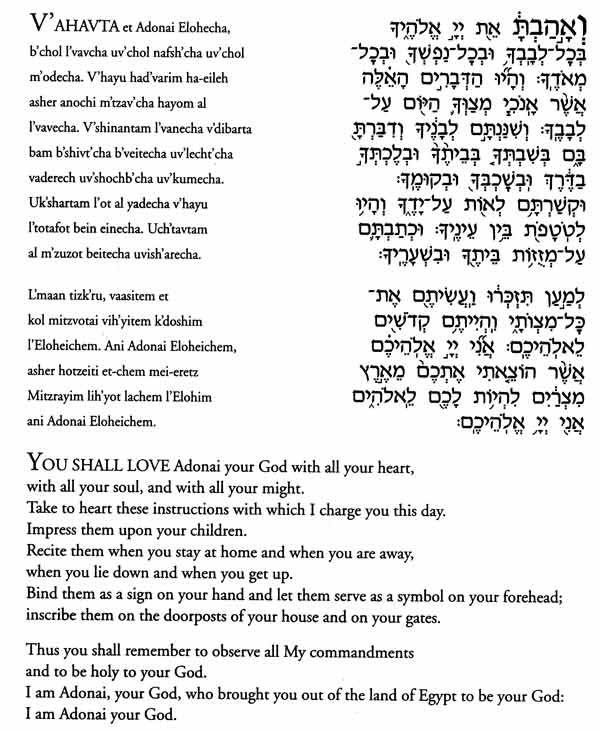

I discussed the “Shema” prayer in a previous article as a way to connect to all Jewish generations that came before us. But there are two even more important features of the prayer which immediately follows: V’Ahavta.

First, although you recite it on your own, it is phrased in second person imperative, as if it were designed to cultivate some voice inside of your head to remind you to do the right thing. This is important, since this is one of the prayers that most Jews know by heart, and thus, over time, it does actually become a “voice in our head”.

Second, its central theme is the unity of heart, soul and mind (I prefer “mind” to “might” in the translation). In other words you cannot live in a state of dissonance between your emotions and your rationality.

In order to achieve this kind oneness of thought and emotion, I believe you should try to reconcile your conception of God with the words of the prayers. I’m not saying you will always succeed in relating emotionally to every verse of every prayer (especially if you understand the Hebrew), but it’s worth trying. Paradoxically, repeating over and over the same Hebrew words that have been uttered millions of times by Jews throughout history may actually change how we feel about saying those very words. Don’t be surprised if you are surprised by your own reaction. Like I said, it’s a paradox.

If you are an agnostic or atheist and suspend your disbelief while you are attending services, then you will have a nagging feeling in the back of your mind that you are somehow cheating, and some of the positive psychological effects mentioned before may be diminished (although Ariely observed that swearing on a Bible seemed to even improve the cheating statistics of atheists). This is why Judaism insists on unity of emotion and rationality.

If your rational mind insists that you are an atheist or an agnostic, then you should adopt a conception of God  that recognizes it is a man-made abstraction that is neither mystical nor creationist nor interventionist, and then everything should fall into place with respect to your ability to recognize the value of Jewish Prayer.

that recognizes it is a man-made abstraction that is neither mystical nor creationist nor interventionist, and then everything should fall into place with respect to your ability to recognize the value of Jewish Prayer.

Everything, that is, except the most important question: Why would you call God by his name and speak to him in the personalized language of the prayers if it is an abstract entity?

I’m not saying I have the “ultimate” answer to this question, but the best answer I have come across so far is based on Martin Buber’s book I and Thou as explained by Rabbi Samuel Karff in his book Agada: The Language Of Jewish Faith.

The basic idea is that human beings experience two kinds of relations: I-It and I-Thou. Relations of the form I-It designate objects. Things that have some utility or usefulness to our lives. In contrast, I-Thou relations are based on a spiritual or emotional connection, as in the case of human-to-human relations. Think of I-It as scientific and detached, while I-Thou is all about love and emotion. For example, Mozart’s 40th Symphony can be analyzed in I-It terms by studying its themes, harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration, but when you are listening to it in a non-educational setting, you might relate to it as I-Thou: a living, breathing entity with whom you have an emotional relationship that lasts your whole life.

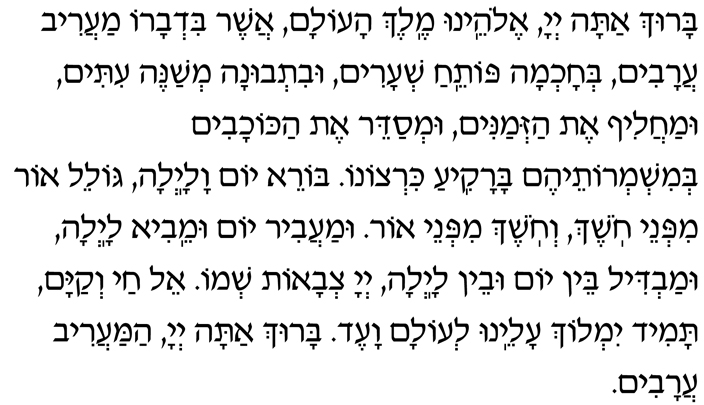

This analogy carries over to the conception of God in Jewish Prayer. In our scientific world, our relationship to the earth, the sun, and the universe is purely I-It, based on astronomy, physics, chemistry and biology. But in our prayers, we are trying to express gratitude for the fact that we have days and nights, and that our bodies feel tired at the end of the day and want to sleep, and that we wake up again the next morning without a meteor having crashed into the earth or our house destroyed by a tornado. This is an I-Thou relationship. Yes, we understand that earth’s rotation around its axis causes day and night, and that its rotation around the sun causes seasons. But we are thankful for the entire system, as a whole, working as it does, as if by design, to enable us to live another day. This is why we say the Maariv Aravim blessing before the reading of the Shema.

This analogy carries over to the conception of God in Jewish Prayer. In our scientific world, our relationship to the earth, the sun, and the universe is purely I-It, based on astronomy, physics, chemistry and biology. But in our prayers, we are trying to express gratitude for the fact that we have days and nights, and that our bodies feel tired at the end of the day and want to sleep, and that we wake up again the next morning without a meteor having crashed into the earth or our house destroyed by a tornado. This is an I-Thou relationship. Yes, we understand that earth’s rotation around its axis causes day and night, and that its rotation around the sun causes seasons. But we are thankful for the entire system, as a whole, working as it does, as if by design, to enable us to live another day. This is why we say the Maariv Aravim blessing before the reading of the Shema.

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Ruler of the universe, who speaks the evening into being, skillfully opens the gates, thoughtfully alters the time and changes the seasons, and arranges the stars in their heavenly courses according to plan. You are Creator of day and night, rolling light away from darkness and darkness from light, transforming day into night and distinguishing one from the other. Adonai Tz’vaot is Your Name. Ever-living God, may You reign continually over us into eternity. Blessed are You, Adonai, who brings on evening.

You can think of this prayer as speaking to the universe in an I-Thou capacity. The entire universe, including all of its current and past gravitational and nuclear forces, some of which happened millions of light years ago, have all somehow aligned in such a way as to allow you to live your own personal life here on earth. Even if you interpret Adonai in this prayer as order that emerged from randomness through some process of cosmic evolution, you can still feel an I-Thou gratitude that this order persists, and this gratitude is likely to lead you to a happier life.

There is a lot of parental imagery in Jewish prayers, and again, you can choose to think of it as evoking the strongest of all our “I-Thou” relationships: those we have with our parents and children. Every parent knows the singular joy of seeing your baby for the first time, and most of us know (or will know) the singular sadness of losing a parent or a loved one. Those two emotional extremes are somehow mysteriously “built into us” just as they are built into our life cycle “from ashes to ashes”. We have no intellectual control over them. They control us. Every Jewish prayer service is designed to take us up and down the emotional roller-coaster of an entire life-cycle. Even on the most joyous holiday, we pause to say Kaddish. Happiness and sadness always go hand in hand in every Jewish prayer service, just as they do in our own lives, and just as they do in the history of the Jewish people.

Jewish Prayer gives us a unique language and a private and communal setting to express gratitude, acceptance, hope and morality. Unlike meditation or other methods of “emptying” your mind, Jewish prayer seeks to “fill” it, even to overwhelm it, both intellectually and emotionally.

By offering the most powerful texts that have withstood the test of centuries, and putting those words together with liturgical melodies that put us in a maximally receptive emotional state, and doing all of that in a social setting of a beautiful synagogue full of awe and historical continuity, Jewish Prayer gives us the tools to enhance our personal happiness and behave more ethically towards each other.