What if, instead of the story we all know about how Bill Gates bought the DOS operating system from IBM, a different press-release had been circulated? One saying that God had revealed himself to Bill, and showed him a field full of glowing faces, and told him that someday all dwellers of the earth would spend 10 hours a day in front of boxes that would make their faces glow, and each of them would pay him a tax for that privilege?

What if a new biography of Steve Jobs came out claiming that God revealed himself to Steve, and told him that he would remote-control the minds of teenagers worldwide at the dinner table, by making them gaze into a small white box which he would permanently implant in their hands?

These are silly examples, but we all know that every book or news story we read depends on the point of view of the writer. The Bible is no exception. In the last century, academic biblical research has made great strides in identifying the points of view and influences of biblical writers and editors.

Books such as Marc Brettler’s How To Read The Jewish Bible and James Kugel’s How To Read The Bible explain the literary, linguistic and archeological tools used in modern academic Bible study. One of these tools is the Documentary Hypothesis of biblical editors.

You can watch an excellent 24-chapter video lecture series which covers the same material by Prof. Christine  Hayes at Open Yale Courses.

Hayes at Open Yale Courses.

Liora Ravid’s excellent book Daily Life in Biblical Times seeks to uncover some of the true underlying biblical stories and strip them of their religious and editorial bias.

For many people with a modern scientific outlook on life, it is natural to think of revelation as a literary device that was added to the story when it was written or edited. Consider how the biblical stories were written. Do you imagine a CNN reporter following Moses to the desert? Do you imagine paparazzi waiting outside of Jacob’s tent in the morning to see which woman will emerge? Most likely, these stories existed as oral traditions for a long time before they were written. And even if they were faithfully written down close to when they occurred, there was probably a process of editing which lasted hundreds of years until a canonical version emerged. One instructive example is Judges 1:26:

And the man… built a city, and called its name Luz; this is its name until this day.

the last three words: “until this day” (עד היום הזה) prove that the text was written long after the events took place, a few generations after the Exodus. So, for the writers and editors, the stories of Moses and his miracles were probably already ancient traditions that were passed down.

The Prophets: Revelation and Miracles

Let’s start with the easier one: miracles. Examination of biblical chronology shows a rapidly diminishing trend in performing miracles. Only ancient stories were told using miracles, while more recent ones were not. Moses and the “early” prophets like Elijah and Elisha performed miracles, while the later “classic” prophets like Isaiah, Ezekiel and Jeremiah did not. Miracles were an ancient story-embellishment tradition that was mostly frowned upon in the second temple period. The Maccebees, for example, did not believe in divine miracles (I explained the miracle of Hanukkah elsewhere). By those days, one to two thousand years after Moses, Jews had already been exposed to Greek philosophy, and were deeply rooted in rational discourse of biblical law. There was no place for magical mystery tours of super-natural experiences in their world. This may help explain why most Jews did not react favorably to a certain Nazarene Jew who claimed, anachronistically, to be an “early” miracle-performing prophet.

In order to analyze the phenomenon of prophecy as a whole, we need to understand the various roles prophets played. A prophet is “a poet, preacher, patriot, statesman, social critic and moralist” writes Abraham Joshua Heschel in his book The Prophets.

Prophets didn’t actually make their living predicting the future. They were a form of political opposition and moral compass. They identified political trends in the surrounding nations, and social trends within their own society. Their main problem was that they had no formal authority. The only prophet who was also a political leader was Moses. Samuel may have had some political clout, but the later prophets had no political standing at all. Some, like Jeremiah, ended up in jail for incitement against the king.

Prophets also had no religious authority. That was in the hands of the priests. The priests dealt with rituals and sacrifices, but not with moral or political issues. This is probably why the prophets had to resort to poetic, dramatic and ecstatic devices to get people to listen to their message of moral chastisement. Indeed the poetic language of the prophets is some of the most beautiful and moving in the entire Bible. The book of Lamentations, attributed to Jeremiah, paints a more vivid picture of post-destruction Jerusalem than any Hollywood production could ever achieve. It is made all the more powerful when read in conjunction with Jeremiah’s prophecies before and after the destruction.

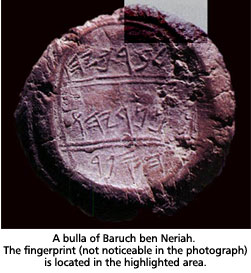

Richard Friedman in his book Who Wrote the Bible goes so far as to claim that it was Jeremiah’s scribe, Baruch Ben Neriah, who wrote, besides the book of Jeremiah, the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, I & II Samuel, and I & II Kings. His bulla was discovered in 1975, providing archeological corroboration for his existence in that period:

Richard Friedman in his book Who Wrote the Bible goes so far as to claim that it was Jeremiah’s scribe, Baruch Ben Neriah, who wrote, besides the book of Jeremiah, the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, I & II Samuel, and I & II Kings. His bulla was discovered in 1975, providing archeological corroboration for his existence in that period:

The Talmud, in Megila 14a, explains that the criterion for writing down prophecy was to educate future generations: “Prophecy that was needed for generations was written, if not needed it was not written” (נבואה שהוצרכה לדורות נכתבה, ושלא הוצרכה לא נכתבה).

There is archeological proof that prophecy was a not just a Jewish phenomenon, but also common in many of the neighboring cultures. For example, Akkadian prophetic texts were found in Mari, which describe professional prophets as divine messengers.

Whether you believe that prophets really had divine revelations, or that they used revelation to gain moral authority, or that revelation was a literary device added by later editors, we know one thing for sure: prophecy was no longer acceptable by second temple period. Like miracles, prophecy was out of Judaism for good.

The Talmud: No more Prophets. No more Miracles. No more Revelation.

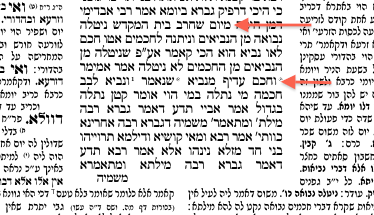

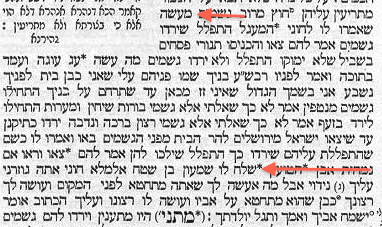

In Baba Batra 12a, the Talmudic sages make it clear that prophecy will never return: “Once the Temple was destroyed, prophecy was taken from prophets and given to sages”. The second red arrow below says: “A sage is preferred to a prophet”.

The second side of the page (Baba Batra 12b) goes even further and says that “Once the Temple was destroyed, prophecy wa s taken from prophets and given to fools and children”. From that time onward, a Jew would be mocked if he claimed divine revelation.

s taken from prophets and given to fools and children”. From that time onward, a Jew would be mocked if he claimed divine revelation.

New laws would have to be derived from ancient laws using legal arguments and debate. This laid the foundation of modern constitutional law. The Bible was considered the Jewish constitution, and every new law had to be derived from it, in word and in spirit.

But what did the Rabbis actually do when someone claimed divine revelation or miracles? They excommunicated him from Jewish society. Two famous Talmudic stories demonstrate this clearly.

The first is the story of Choni ha-M’agel (חוני המעגל). This was towards the end of Greek rule, around 1st century BC, the period of the Zugot, and the Nasi (head of the Sanhedrin) was Shimon Ben Shetach. The incident is told in Taanit 19:

During a drought, Choni drew a circle in the sand, stood inside it, and gave an ultimatum to God that he would not move until it rained. It began to drizzle, Choni told God that this was not good enough. He asked for more rain. It began to pour. Choni complained that this was not what he requested either! He asked for a calm rain, at which point the rain calmed to a normal rain.

During a drought, Choni drew a circle in the sand, stood inside it, and gave an ultimatum to God that he would not move until it rained. It began to drizzle, Choni told God that this was not good enough. He asked for more rain. It began to pour. Choni complained that this was not what he requested either! He asked for a calm rain, at which point the rain calmed to a normal rain.

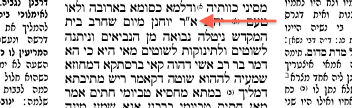

The second red arrow points to the aftermath. Shimon Ben Shetach himself heard of this incident and sent him a grave warning: I should excommunicate you from  society for this act! (He ends up forgiving him because of his social status). The threat of Cherem (excommunication) is second only to death in the Talmud. It means being cut off from Jewish life completely. The reason the head of the Sanhedrin, the number one Jewish authority of the day, would make such a grave threat to Choni was that it was unacceptable for a person to have a dialog with God. To give him an ultimatum. To ask him to do better. Shimon Ben Shetach ends by scolding him that he is like a child having a tantrum in front of his father. By his actions, Choni implied that he could harness super-natural powers, and that was completely at odds with the abstract God of second temple Jews.

society for this act! (He ends up forgiving him because of his social status). The threat of Cherem (excommunication) is second only to death in the Talmud. It means being cut off from Jewish life completely. The reason the head of the Sanhedrin, the number one Jewish authority of the day, would make such a grave threat to Choni was that it was unacceptable for a person to have a dialog with God. To give him an ultimatum. To ask him to do better. Shimon Ben Shetach ends by scolding him that he is like a child having a tantrum in front of his father. By his actions, Choni implied that he could harness super-natural powers, and that was completely at odds with the abstract God of second temple Jews.

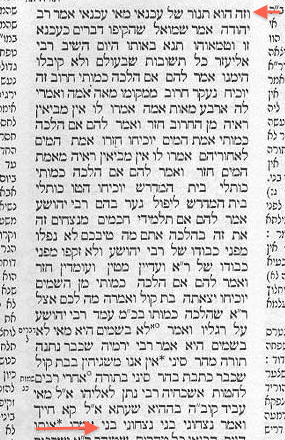

An even more extreme case in point is the story of Achnai’s Oven which took place a generation later at Yavneh around 1st-2nd century CE, after the destruction of the second temple. Rabbi Eliezer was not as lucky as Choni. He summoned God in an argument with other Rabbis, and was excommunicated until his dying day.

The story tells of a rabbinic counsel meeting where Rabbi Eliezer was frustrated because he kept getting overruled by the majority. On this specific case of “Achnai’s Oven” (the specifics don’t matter here), he says: if I am right, let this tree uproot and fly away. And the tree flies away. The rabbis are not amused: you can’t bring evidence from a tree, they tell him. He doesn’t give up: if I am right, let the river flow upward. The river flows upwards. The rabbis are equally unimpressed: you can’t prove a legal claim by water flowing upward. He persists: if I am right, let the walls cave in. The rabbis shrug it off and Rabbi Yehushua ridicules him even further by humorously scolding the walls for threatening to fall. Finally, Rabbi Eliezer goes all out: if I am right, a voice from heaven (בת קול) will say so. A voice from heaven is heard saying: why do you torment Rabbi Eliezer? Halacha should be like he says. The rabbis talk back to the voice saying: “Lo Bashamaim Hi” (לא בשמים היא), authority is not in the heavens any more, a quote from Deuteronomy 30:12. They jokingly say to God: you wrote in the bible that the law goes by the majority (אחרי רבים להטות) – so stay out of our argument. And God smiles and kvells to himself twice: my children have outwitted me, my children have outwitted me (נצחוני בני, נצחוני בני).

I hope you agree that the humor in this dialog is worthy of Woody Allen. The other Rabbis treat Rabbi Eliezer as a lunatic who went off the deep end. Summoning God personally into a Talmudic argument is too ridiculous to warrant a serious response. God does not make appointments and show up to support his fans. That is a concrete personification of God synonymous with idolatry. The Rabbis laugh it off and play along. But the aftermath is not so funny. Rabbi Eliezer, in spite of his impeccable credentials and past glory, is excommunicated and dies a lonely and bitter man. He paid the ultimate price for claiming he could summon up super-natural powers, in an era when Judaism no longer tolerated such irrational behavior.